This is the final installment of a three-part essay advocating a radical revisionism of the first millennium AD. In Part 1 and Part 2, I examined a series of fundamental problems in our standard history of the greater part of the first millennium AD. Here I present what I believe is the best solution to these problems. We are so used to rely on a universally accepted global chronology covering all of human history that we take this chronology as a given, a simple representation of time itself, as self-evident as the air we breathe. In reality, this chronology, which allows us to place with relative precision on a single time scale all major events in the histories of all peoples, is a sophisticated cultural construct that was not achieved before the late sixteenth century. Jesuits played a prominent role in that computation, but the main architect of the chronology we are now familiar with was a French Huguenot named Joseph Scaliger (1540-1609), who set out to harmonize all available chronicles and calendars (Hebrew, Greek, Roman, Persian, Babylonian, Egyptian). His main works on chronology, written in Latin, are De emendatione temporum (1583) and Thesaurus temporum (1606). The Jesuit Denys Pétau (1583-1652) built on Scaliger’s foundation to publish his Tabulae chronologicae, from 1628 to 1657. So our global chronology, the backbone of textbook history, is a scientific construct of modern Europe. Like other European norms, it was accepted by the rest of the world during the period of European cultural domination. The Chinese, for example, had already compiled, during the Song dynasty (960-1279), a long historical narrative, but it was Jesuit missionaries who reshaped it to fit in their BC-AD calendar, resulting in the thirteen volumes of the Histoire Générale de la Chine by Joseph-Anne-Marie de Moyriac de Mailla, published between 1777 and 1785. [1] Once Chinese history was securely riveted to Scaligerian chronology, the rest followed. But some peoples had to wait until the 19th century to find their place in that framework; the Indians had very ancient records, but no consistent chronology until the British gave them one. Truth be told, the chronology of ancient empires was never completely settled. In The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended, Isaac Newton (1642-1727) had suggested to reduce drastically the by-then-accepted antiquity of Greece, Egypt, Assyria, Babylon and Persia. Today, ancient chronology is still open to debate in the academic community (read for instance about David Rohl’s “new chronology”). But as we approach the Common Era, the chronology is considered untouchable, except for minor adjustments, because of the abundance of written sources. However, until the ninth century AD, no primary source provides absolute dates. Events are dated relatively to some other event of local importance, such as the foundation of a town or the accession of a ruler. Dating recent events in anno domini (AD) only became common in the eleventh century. So the general timeline of the first millennium still relies on a great deal of interpretation, not to mention trust in the sources. Like for earlier eras, it was fixed centuries before the beginning of scientific excavations (19th, mainly 20th century), and, as we shall see, its authority is such that archeologists surrender to it even when their stratigraphic data contradicts it. Dendrochronology (tree-rings dating) and radiocarbon dating (for organic materials) are of little help, and are unreliable anyway because they are relative, interdependent, and calibrated on the standard timeline one way or another. For the reasons exposed in Part 1, Part 2 and below, some researchers think that it is high time for a paradigm shift in first millennium chronology. The best-known of these revisionists is the Russian mathematician Anatoly Fomenko (born 1945). With his associate Gleb Nosovsky, he has produced tens of thousands of pages in support of his “New Chronology” (check their Amazon page). In my view, Fomenko and Nosovsky have signaled a great number of major problems in conventional chronology, and provided plausible solutions to many of them, but their global reconstruction is extravagantly Russo-centric. Their confidence in their statistical method (a good presentation in this video) is also exaggerated. Nevertheless, Fomenko and Nosovsky must be credited for having provided stimulus and direction for many others. For a first approach to their work, I recommend volume 1 of their series History: Fiction or Science ( here on archive.org), especially chapter 7, “‘Dark Ages’ in Mediaeval History”, pp. 373-415. One major discovery of Fomenko and Nosovsky is that our conventional history is full of doublets, produced by the arbitrary end-to-end alignment of chronicles that tell the same events, but are “written by different people, from different viewpoints, in different languages, with the same characters under different names and nicknames.” [2] Whole periods have been thus duplicated. For example, drawing from the previous work of Russian Nikolai Mozorov (1854-1946), Fomenko and Nosovsky show a striking parallel between the sequences Pompey/Caesar/Octavian and Diocletian/Constantius/Constantine, leading to the conclusion that the Western Roman Empire is, to some extent, a phantom duplicate of the Eastern Roman Empire. [3] According to Fomenko and Nosovsky, the capital of the one and only Roman Empire was founded on the Bosporus some 330 years before the foundation of its colony in the Latium. Starting from the age of the crusades, Roman clerics, followed by Italian humanists, produced an inverted chronological sequence, using the real history of Constantinople as the model for their fake earlier history of Italian Rome. A great confusion ensued, as “many mediaeval documents confuse the two Romes: in Italy and on the Bosporus,” both being commonly called Rome or “the City”. [4] A likely scenario is that the prototype for Titus Livy’s History was about Constantinople, the original capital of the “Romans”. The original Livy, Fomenko conjectures, was writing around the tenth century about Constantinople, so he was not far off the mark when he placed the foundation of the City ( urbs condita) some seven centuries before his time. But as it was rewritten by Petrarch and reinterpreted by later humanists (read “How fake is Roman Antiquity?”), a chronological chasm of roughly one thousand year was introduced between the foundation of the two “Romes” (from 753 BC to 330 AD). However, even the dates for Constantinople are wrong, according to Fomenko and Nosovky, and the whole sequence happened much more recently: Constantinople was founded around the tenth or eleventh century AD, and Rome, 330 or 360 years later, i.e. around the fifteenth or sixteenth century AD. Here, as often, Fomenko and Nosovsky may be spoiling their best insights by exaggeration. The German ZeitenspringersIn the mid-1990s, independently from the Russian school, German scholars Heribert Illig, Hans-Ulrich Niemitz, Uwe Topper, Manfred Zeller and others also became convinced that something is wrong with the accepted chronology of the Middle Ages. Calling themselves the “Zeitenspringer” (time jumpers), they suggested that approximately 300 years — from 600 to 900 AD — never existed. English summaries of their approach have been produced by Niemitz ( “Did the Early Middle Ages Really Exist?” 2000), and in Illig ( “Anomalous Eras – Best Evidence: Best Theory” 2005). The German discussion originally focused on Charlemagne ( Illig’s book). Sources on Charlemagne are often contradictory and unreliable. His main biography, Eginhard’s Vita Karoli, supposedly written “for the benefit of posterity rather than to allow the shades of oblivion to blot out the life of this King, the noblest and greatest of his age, and his famous deeds, which the men of later times will scarcely be able to imitate” (from Eginhard’s foreword), is recognizably modeled on Suetonius’ life of the first Roman emperor Augustus. Charlemagne’s “empire” itself, lasting only 45 years, from 800 to its dislocation in three kingdoms, defies reason. Ferdinand Gregorovius, in his History of the City of Rome in the Middle Ages in 8 volumes (1872), writes: “The figure of the Great Charles can be compared to a flash of lightning who came out of the night, illuminated the earth for a while, and then left night behind him” (quoted by Illig). Is this shooting star just an illusion, and the legends about him virtually devoid of relation to history? The main problem with Charlemagne is with architecture. His Palatine Chapel in Aachen exhibits a technological advance of 200 years, with for example arched aisles not seen before the 11th century. On the opposite, Charlemagne’s residence in Ingelheim was built in the Roman style of the 2nd century, with materials supposedly recycled from the 2nd century. Illig and Niemitz challenge such absurdities and conclude that Charlemagne is a mythical predecessor invented by the Ottonian emperors to legitimate their imperial claims. All Carolingians of the 8th and 9th and their wars are also fictitious, and the timespan of roughly 600-900 CE, is a phantom era. Gunnar Heinsohn objects to this theory on numismatic ground: about 15,000 coins have been found bearing the name Karlus (alternatively Karolus or Carlus) Magnus. Gunnar Heinsohn’s breakthroughGunnar Heinsohn, from the University of Bremen, is in my view the most interesting and convincing scholar in the field of chronological revisionism. His recent articles in English are posted on this website, and his 2016 conference in Toronto makes a good introduction. Heinsohn focuses on hard archeological evidence, and insists that stratigraphy is the most important criterion for dating archeological finds. He shows that, time and again, stratigraphy contradicts history, and that archeologists should have logically forced historians into a paradigm shift. Unfortunately, “In order to be consistent with a pre-fabricated chronology, archaeologists unknowingly betray their own craft.” [5] When they dig up the same artifacts or building structures in different parts of the world, they assign them to different periods in order to satisfy historians. And when they find, in the same place and layer, mixtures of artifacts that they have already attributed to different periods, they explain it away with the ludicrous “heirloom theory,” or call them “art collections.” “Archaeologists are particularly confident of correctly dating finds from 1st-millennium excavation sites when they find coins associated with them. A coin-dated layer is considered to be of utmost scientific precision. But how do scholars know the dates of the coins? From coin catalogues! How do the authors of these catalogues know how to date the coins? Not according to archaeological strata, but from the lists of Roman emperors. But how are the emperors dated and then sorted into these lists? Nobody knows for sure.” [6]

Quite often, archeologists unearth coins of supposedly widely different dates in the same settlement strata or the same tombs. One example is the famous leather purse of Childeric, a Frankish prince reigning from 458-481 AD. For Heinsohn, these coins are not a “coin collection” but “indicate the simultaneity of Roman Emperors artificially dispersed over two epochs — Imperial Antiquity and Late Antiquity.” [7]Heinsohn’s work is not easy to summarize, because it is a work in progress, because it covers virtually all regions of the globe, and because it is abundantly illustrated and referenced with historical and archeological studies. Nothing can replace a painstaking study of his articles, completed with personal research. All I can do here is try to reflect the scope and the depth of his research and the significance of his conclusions. Rather than paraphrase him, I will quote extensively from his articles. From now on, only quotations from other authors will be indented. All illustrations, except the next one and the last one, are borrowed or adapted from his articles. The best starting point is his own summary ( “Heinsohn in a nutshell”): “According to mainstream chronology, major European cities should exhibit — separated by traces of crisis and destruction — distinct building strata groups for the three urban periods of some 230 years that are unquestionably built in Roman styles with Roman materials and technologies (Antiquity/ A>Late Antiquity/ LA>Early Middle Ages/ EMA). None of the ca. 2,500 Roman cities known so far has the expected three strata groups super-imposed on each other. … Any city (covering, at least, the periods from Antiquity to the High Middle Ages [ HMA; 10th/11th c.]) has just one ( A or LA or EMA) distinct building strata group in Roman format (with, of course, internal evolution, repairs etc.). Therefore, all three urban realms labeled as A or LA or EMA existed simultaneously, side by side in the Imperium Romanum. None can be deleted. All three realms (if their cities continue at all) enter HMA in tandem, i.e. all belong to the 700-930s period that ended in a global catastrophe. This parallelity not only explains the mind-boggling absence of technological and archaeological evolution over 700 years but also solves the enigma of Latin’s linguistic petrification between the 1st/2nd and 8th/9th c. CE. Both text groups are contemporary.” [8]In other words, from other articles: “The High Middle Ages, beginning after the 930s A.D., are not only found –– as would be expected –– contingent with, i.e., immediately above the Early Middle Ages (ending in the 930s). They are also found –– which is chronologically perplexing –– directly above Imperial Antiquity or Late Antiquity in locations where settlements continued after the 930s cataclysm.” [9] “There is — in any individual site — only one period of some 230 years (all of them with Roman characteristics, such as imperial coins, fibulae, millefiori glass beads, villae rusticae etc.) that is terminated by a catastrophic conflagration. Since the cataclysm dated to the 230s shares the same stratigraphic depth as the cataclysms dated to the 530s or the 930s, some 700 years of 1st millennium history are phantom years.” [10] The first millennium, in other words, lasted only about 300 years. “Following stratigraphy, all earlier dates have to come about 700 years closer to the present, too. Thus, the last century of Late Latène (100 to 1 BCE), moves to around 600 to 700 CE.” [11]All over the Mediterranean world “three blocks of time have left — in any individual site — just one block of strata covering some 230 years.” Wherever they are found, the strata for Imperial Antiquity and Late Antiquity lie just underneath the tenth century and therefore really belong to the Early Middle Age, that is, 700-930 AD. The distinction between Antiquity, Late Antiquity and Early Middle Age is a cultural representation that has no basis in reality. Heinsohn proposes contemporaneity of the three periods, because they “are all found at the same stratigraphic depth, and must, therefore, end simultaneously in the 230s CE (being also the 520s and 930s).” [12] “Thus, the three parallel time-blocks now found in our history books in a chronological sequence must be brought back to their stratigraphical position.” [13] In this way, “the early medieval period (approx. 700-930s AD) becomes the epoch for which history can finally be written because it contains Imperial Antiquity and Late Antiquity, too.” [14]As a result of stretching 230 years into 930 years, history is now distributed unevenly, each time-block having most of its recorded events localized in one of three geographical zones: Roman South-West, Byzantine South-East, and Germanic-Slavic North. If we look at written sources, “we have [for the 1st-3rd century] a spotlight on Rome, but know little about the 1st-3rd century in Constantinople or Aachen. Then we have a spotlight on Ravenna and Constantinople, but know little about the 4th-7th century in Rome or Aachen. Finally, we have a spotlight on Aachen in the 8th-10th century, but hardly know any details from Rome or Constantinople. I turn on all the lights at the same time and, thus, can see connections that were previously considered dark or completely unrecognizable.” [15]Each period ends with a demographic, architectural, technical, and cultural collapse, caused by a cosmic catastrophe and accompanied by plague. Historians “have identified major mega-catastrophes shaking the earth in three regions of Europe (South-West [230s]; South-East [530s], and Slavic North [940s]) within the 1st millennium.” [16] “The catastrophic ends of (1) Imperial Antiquity, (2) Late Antiquity, and (3) the Early Middles Ages sit in the same stratigraphic plane immediately before the High Middle Ages (beginning around 930s AD).” [17] Therefore these three devastating collapses of civilization are one and the same, which Heinsohn refers to as “the Tenth Century Collapse.” Heinsohn’s identification of three time-blocks that should be synchronized is not to be taken as an exact parallelism: “This assumption does not claim a pure 1:1 parallelism in which events reported for the year 100 AD could simply be supplemented with information for the year 800 AD.” [18] Stratigraphic identity only means that all real events that are dated to Imperial Antiquity or Late Antiquity happened in fact during the Early Middle Ages (from the stratigraphic viewpoint). Moreover, all three time-blocks do not have the same length. That is because Late Antiquity (from the beginning of Diocletian’s reign in 284 to the death of Heraclius in 641) is some 120 years too long, according to Heinsohn. The Byzantine segment from the rise of Justinian (527) to the death of Heraclius (641) was in reality shorter and overlapped with the period of Anastasius (491-518). In other words, not only the first millennium as a whole, but Late Antiquity itself has to be shortened. Duplicates account for its phantom years. Thus the Persian emperor Khosrow I (531-579) fought by Justinian is identical to the Khosrow II (591-628) fought by his immediate successors — regardless of the fact that archeologists decided to ascribe the silver drachmas to Khosrow I and the gold dinars to Khosrow II. [19]Other duplicates within Late Antiquity include the Roman emperor Flavius Theodosius (379-395) being identical to the Gothic ruler of Ravenna and Italy Flavius Theodoric (471-526), who bears the same name, only with the additional suffix riks, meaning king. “At some point in the half millennium with manipulations of the original texts that can no longer be counted or reconstructed, two names of one person have become two persons with different names placed one behind the other.” The Gothic wars have also been duplicated: with the war fought by Odoacer and his son Thela in the 470, and the one fought by ToTila in the 540s, “we are not dealing with two different Italian wars, but with two different narratives about the same war, which were connected chronologically one after the other.” [20]

This author’s visual of the simultaneous three 230-year time-blocks

The strength or Heinsohn’s approach, as compared to Illig and Niemtiz’s, is that he doesn’t really delete history: “If one removes the span of time that has been artificially created by mistakenly placing parallel periods in sequence, only emptiness is lost, not history. By reuniting texts and artifacts that have now been chopped up and scattered over seven centuries, meaningful historiography becomes possible for the first time.” [21] In fact, “a much richer image of Roman history emerges. The numerous actors from Iceland (with Roman coins; Heinsohn 2013d) to Baghdad (whose 9th c. coins are found in the same stratum as 2nd c. Roman coins; Heinsohn 2013b) can eventually be drawn together to weave the rich and colourful fabric of that vast space with 2.500 cities, and 85.000 km of roads.” [22]Applied to Rome, Heinsohn’s theory solves a conundrum that has always puzzled historians: the absence of any vestige datable from the late third century to the tenth century (mentioned in Part 1): “Rome of the first millennium CE builds residential quarters, latrines, water pipes, sewage systems, streets, ports, bakeries etc. only during Imperial Antiquity (1st-3rd c.) but not in Late Antiquity (4th-6th c.) and in the Early Middle Ages (8th-10th c.). Since the ruins of the 3rd century lie directly under the primitive new buildings of the 10th century, Imperial Antiquity belongs stratigraphically to the period from ca. 700 to 930 CE.” [23] “The heart of the Imperium Romanum has no new construction for the seven centuries between the 3rd and the 10th c. CE. The urban material of the 3rd c. is stratigraphically contingent with the early 10th in which it was wiped out.” [24] In the illustration below, the floor of Trajan’s Forum (Piano Antico 2nd/3rd c. AD) is directly covered by the dark mud ( fango) layer of the cataclysm that sealed Roman Civilization (more on it later).

In order to fill up their artificially stretched millennium, modern historians often have to do violence to their primary sources. As Fomenko already pointed out, the Getae and the Goths were considered the same people by Jordanes — himself a Goth — in his Getica written in the middle of the 6th century. Other historians before and after him, such as Claudian, Isidore of Seville and Procopius of Caesarea also used the name Getae to designate the Goths. But Theodor Mommsen has rejected the identification: “The Getae were Thracians, the Goths Germans, and apart from the coincidental similarity in their names they had nothing whatever in common.” [25] Yet archeologists are puzzled by the fact that the Getae and the Goths inhabit the same area at 300 years distance, and there is no explanation for how the Getae disappeared before the Goth appeared, and for the lack of demography during the 300-year interval. Besides, there is evidence, contrary to what Mommsen claims, of great resemblance between their culture, including in clothing, as Gunnar Heinsohn points out: Goths in the 3rd/4th c. “made great efforts to dress, from head to toe, like their mysteriously missing predecessors” (the 1st/3rd-c. Getae), and continued “to manufacture 300 year older ceramics, rolling back technological evolution to pre-Christian La Tène earthenware.” [26] According to Heinsohn, “The identity of Getae and Goths can help to solve some of the most stubborn enigmas of Gothic history,” such as strong parallel between Rome’s Getic-Dacian wars in the first century AD and Rome’s Gothic wars some 300 years later. The Dacian leader Decebalus (meaning “The Powerful”) may be identical to the Goth Alaric (meaning “King of all”). By such processes, “different sources dealing with the same events have been split (and altered) in such a way that the same event is described twice, albeit from different angles, thereby creating a chronology that is twice as long as the actual course of history that can be substantiated by archaeology.” [27]

Getian prisoner and Gothic warrior, both wearing the same clothes, including the Phrygian hat

Constantinople“While no new residential areas with latrines, water systems and streets were built in Rome during Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages, they are missing in Constantinople during Imperial Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. […] Both cities have these basic components of urbanity in only one of the three epochs of the first millennium. Although in Rome they are dated to Imperial Antiquity, whilst in Constantinople they are dated to Late Antiquity, from the point of view of architecture and building technology they are nearly indistinguishable.” [28] That is because, in reality, they “share the same stratigraphical horizon.” [29]There are, however, non-residential constructions in Byzantium dated from Imperial Antiquity. The most important is its first recorded aqueduct, built under Hadrian (117-138 AD). “This is considered a mystery because Byzantium’s actual founder, Constantine the Great (305-337 AD), did not expand the city until 200 years later.” In reality, “Hadrian’s aqueduct carries water to a flourishing city 100 years after Constantine, and not to a supposed wasteland centuries earlier. The mystery disappears. When Justinian renovates the great Basilica Cistern, which gathers water from Hadrian’s aqueduct, he does so not 400 years, but less than 100 years after it was built.” [30]The Early Middle Ages are known as Byzantium’s Dark Ages, beginning in 641 after the reign of Heraclius, and ending with the Macedonian Renaissance under Basil II (976-1022 AD). [31] In the words of historian John O’Neill, “About forty years after the death of Justinian the Great, from the first quarter of the seventh century, [for] three centuries, cities were abandoned and urban life came to an end. There is no sign of revival until the middle of the tenth century.” [32] For Heinsohn, this period, like most other “dark ages”, is a phantom age. The Justinian dynasty starting with Justin I (AD 518-527) is identical to the Macedonian dynasty, which we can count from Constantine VII (913-959), initiator of the Macedonian Renaissance. The 400-year period between Justinian (527-565 AD) and Basil II lasted in reality only 70 years, corresponding to the Tenth Century Collapse. Besides archeology, there are also “anachronisms and puzzles in the development of the laws of Justinian (527-535 CE),” written in 2nd-c. Latin. “Not a single jurist from the 300 years between the Severan early 3rd century and Justinian’s 6th century textbook date is included in the Digestae. Moreover, no post-550s jurist put his hand to the Digestae.” So that “There are, from the Severans to the end of the Early Middle Ages, some 700 years without comments by Roman jurists.” In addition: “It is a mystery why Justinian’s Greek subjects had to wait 370 years [until the 900s CE], only to receive a version of the laws in Koine Greek of the 2nd c. out of use since 700 years.” It all “looks bizarre only as long as the stratigraphic simultaneity of Imperial Antiquity, Late Antiquity, and the Early Middle Ages is denied.” [33] That the Severan and the Justinian dynasties are contemporaries explain that both fought a Persian emperor named Khosrow. According to Heinsohn, the foundation of Imperial Rome and Imperial Constantinople are roughly contemporary. It is “a geographical sequence from west to east [that] was turned into a chronological sequence from earlier to later.” [34] “Diocletian did not reside in ruins, but lived at the same time as Augustus. His capital was not Rome. He had residences in Antioch, Nicomedia, and Sirmium. From there he worked tirelessly for the protection of Augustus’ empire.” [35] Heinsohn’s hypothesis of the contemporaneity of Diocletian in the East and Octavian Augustus in the West (ruling in concert) distinguishes him from Fomenko, who believes that Augustus is a fictitious duplicate of the Roman Emperor residing in Constantinople. Heinsohn also differs from Fomenko in the way he sees the relationship between the two Roman capitals: he accepts Rome’s precedence and assumes that Diocletian was a subordinate of Octavian Augustus. Fomenko, on the other hand, considers that Constantinople was the original center of the empire. This is consistent with Diocletian’s position as the superior of his Western counterpart Maximian. Diocletian was an Eastern Emperor from the beginning. He was born in today’s Croatia, where he built his palace (Split), and hardly ever set foot in Rome. Maximian, sent to rule in Rome, was himself from the Balkans. Ravenna is a special case, because it stands between Rome and Constantinople: it was long under Byzantine control, yet was the “capital of the Occident in Late Antiquity” (Friedrich Wilhelm Deichmann). Ravenna has been called a “palimpsest” for the reason explained by historian Deborah Mauskoppf Deliyannis (Ravenna in Late Antiquity, Cambridge UP, 2014), quoted by Heinsohn: “Ravenna’s walls and churches were usually built of reused brick. Scholars disagree over whether the use of these spolia was symbolic (triumph over Roman paganism, for example) or whether their use simply had to do with the availability and expense of materials. In other words, was their use meaningful, or practical, or both? Did it demonstrate the power of the emperors to control construction of preexisting buildings, or the power of the church to demolish them? Or, by the time Ravenna’s buildings were constructed, were Roman spolia simply considered de rigueur for impressive public buildings. / One striking feature to all these [5th century; GH] buildings is that, like the city walls they were made of bricks that had been reused from earlier [2nd/3rd century; GH] Roman structures. […] It was expected that a noble church would be built of spolia.” [36]

One senses here a desperate effort to force into the accepted chronological framework a situation that doesn’t fit in it. Heinsohn’s revisionism solves this problem: the buildings and their materials are, of course, contemporary, rather than separated by 300 years. There is also a problem with Ravenna’s civil and military port, which could harbor 240 ships according to Jordanes, with its lighthouse praised by Pliny the Elder as rivaling with the Pharos of Alexandria. “However, what is considered strange is that after all port activities ceased around 300 AD it is still being celebrated by mosaics supposedly created in the 5th/6th century. Even Agnellus in the 9th century knows the lighthouse, although the city had supposedly fallen into ruins in the late 6th century.” [37]Andrea Agnellus (ca. 800-850) was a cleric from Ravenna who wrote the history of Ravenna from the beginning of the Empire to his time. After Vespasian (69-79 AD), the emperor of the martyrdom of Peter, Agnellus doesn’t report anything before events dated 500 years later. He writes about saint Apollinaris being sent to Ravenna by saint Peter to found the church of Ravenna, then about the construction of Ravenna’s first church (Sant’Apollinare dated 549 AD), without apparently being aware that half a millennium separated the two. Again, we see here how historians do violence to their sources by inserting phantom times into their chronicles. According to Heinsohn, only approximately 130 years passed between Vespasian and Agnellus.

Mosaic in the Basilica of Sant‘Apollonare Nuove (dated around 500 AD)

Charlemagne and the European Dark AgesIn the footsteps of Illig and Niemitz, Heinsohn notes that Charlemagne’s residence at Ingelheim is built like a Roman villa dating from the 2nd and not from the 9th c. CE. As noticed in a website dedicated to the building, it “was not fortified. Nor was it built on a naturally protected site, which was usually necessary and customary when building castles” ( Fortifications 2009). Heinsohn comments: “It was as if Charlemagne did not understand the vagaries of his own period, and was behaving like a senator still living in the Roman Empire. He insisted on Roman rooftiles but forgot the defenses. Was he not just great but also insane?” [38] No medieval fortification has been found that could be attributed to Charlemagne or any of the Carolingians. Archeologists excavating Ingelheim were “staggered by a building complex that — down to the water supply, and up to the roofing — was ‘based on antique designs’ ( Research 2009), and, therefore, appears to be a reincarnation of 700-year-older Roman outlines from the 1st to 3rd c. CE.” [39] The same is true of his Aachen residence (chapel excluded): “Excavators are realizing that Aachen’s Imperial Antiquity and Aachen’s Early Middle Ages cannot have followed each other at a distance of 700 years, but must have existed simultaneously. This seems incredible, but the material findings, down to the floor tiles, speak with unmistakable clarity: Aachen’s Roman sewer system is so well intact that the early medieval Aacheners ‘tied themselves to the Roman sewer system.’ The same applies to transport routes: ‘A continuous use from Roman times also applies to large parts of the inner city road and path network. […] The Roman road, which has already been documented in the Dome- Quadrum [Palatinate ensemble] in northeast-southwest orientation, was used until the late Middle Ages’.” [40]As mentioned earlier, Heinsohn objects to Illig and Niemitz’s conclusion of the non-existence of Karlus Magnus, on the ground of the great number of coins bearing his name. However, he adds, “These coins are sometimes surprising because they may be found lumped together with Roman coins that are 700 years older.” [41] Deleting 700 years solves this problem, and at the same time matches Charlemagne’s palaces with 2nd/3rd century Roman architecture. The Carolingian era that precedes immediately the Tenth Century Collapse is the era of the Roman Empire. “Today’s researchers see Charlemagne as the promoter of a restoration of the Roman Empire ( restitutio imperii). They see his time as an ingenious and conscious renaissance of a perished civilization. Charlemagne himself, however, knows nothing about such notions. […] Nowhere does he proclaim that he lives many centuries after the glories of imperial Rome.” [42]Just like “Carolingian architects erected buildings and water pipes in the early Middle Ages that were similar in form and technology to those of Imperial Antiquity,” so “Carolingian authors wrote in the early Middle Ages in the Latin style of Imperial Antiquity.” Thus, Alcuin of York ( Flaccus Albinus Alcuinus, 735-804 AD) brought back to life at the court of Charlemagne the classical Latin of Imperial Antiquity (1st-3rd century) after many dark centuries. [43] Alcuin also wrote Propositiones ad acuendos iuvenes, which is seen as the earliest general survey of mathematical problems in Latin. “We do not understand how Alcuin could learn mathematics and write it down in Ciceronian Latin after the crises of the 3rd and 6th century, when there were no more teachers from Athens, Constantinople and Rome to instruct him.” [44]Heinsohn shows that Charles the Great, Charles the Bald, Charles the Fat, and Charles the Simple appear to have the same signature and may be one and the same, although Heinsohn “has not come to a final view on how many Carolinginan Carolus rulers have to be retained.” [45] It must be noted that Karlus is the Latin form of Karl, a Slavic noun meaning “king”, hardly a personal name. Heinsohn remarks: “There have been, we are told, two Frankish lords by the name of Pepin in the territory of Civitas Tungrorum (roughly the diocese of Liège). Each had a son named Charles. One was Charles Martel, the other Charlemagne. Each Charles waged one war against the Saracens on the French-Spanish border, and ten wars against the Saxons. […] This author sees both Pepins, as well as both Charles’, as alter egos.” [46] Moreover, Heinsohn recently suggested that: “Stratigraphically […], Charlemagne and Louis [the Pious] do not belong to the 8th/9th century, but to the 9th/10th century. They live through the turmoil of the plague of Marcus Aurelius and Commodus of the late 2nd century.” [47]That Karlus is called Imperator Augustus does not preclude him being contemporary with others claiming the same title in Italy. Heinsohn mentions that gold coins found in Ingelheim “caused surprise by the imperial diadem worn by Charles making him look like a junior partner of Rome.” [48]

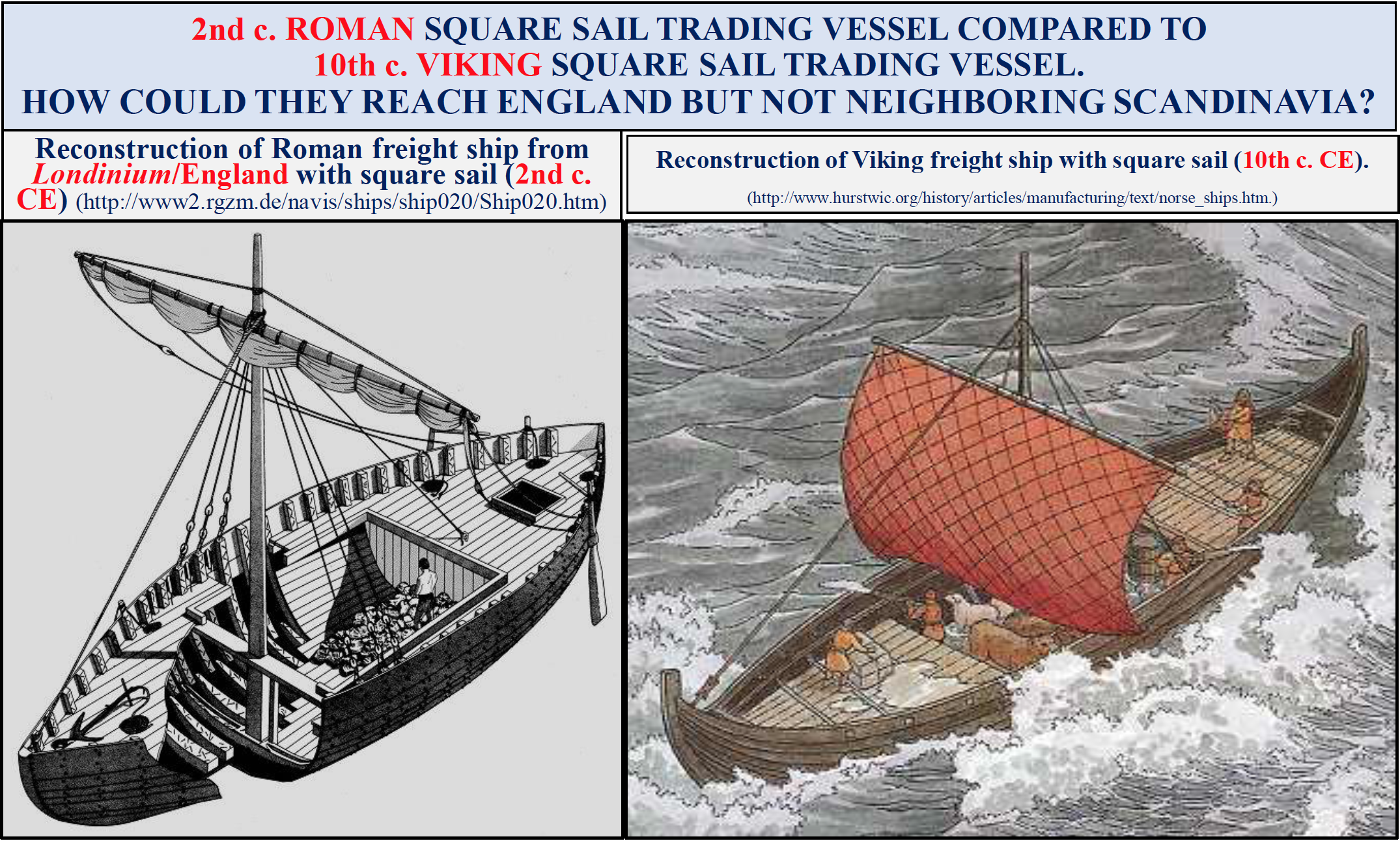

Saxon EnglandSaxons are supposed to start taking over England in 410 AD, yet archeologists cannot find any trace of them in that period. Saxon houses and sacral buildings are missing, there is no trace of their agriculture, and not even of their pottery. [49] Heinsohn solves this problem by suggesting that the earliest Anglo-Saxons of the Early Middle Ages (8th-10th century) were contemporaries of Roman Imperial Antiquity (1st-3rd century); “that would mean that Romans and Anglo-Saxons had fought simultaneously and in competition with each other for control of Celtic Britain.” [50]In Winchester, the city of Alfred the Great (871-899 AD), no archeology remains whatsoever has been found that match his reign. “Nobody knows where the Anglo-Saxon king was able to hold court. Although some scholars try to resort to the idea of a mobile court with no fixed capital anywhere on the British Isles in the 8th to early 10th c. period, the sources give no hint of such homeless rulers. They describe Venta Belgarum/Winchester as the unchallenged capital of Wessex. Since there are no building strata in 9th c. Venta Belgarum/Winchester, the mobile court theory would have to be expanded to a mobile nation theory because Afred’s bureaucrats as well as his subjects are without fixed homesteads, too. Yet, is it possible that entire nations have always been on the move without leaving traces?” [51]Archeologists do find an abundance of buildings in Winchester, but they are in typical 2nd-century Roman style, and, unlike in Charlemagne’s case, archeologists see them as genuine 2nd century rather than imitation of 2nd century. “Yet, the Roman period 2nd/3rd c. building stratum with Roman town houses (domus), temples, and public buildings on a forum with Jupiter column […] is contingent with Winchester’s 10th/11th c. building stratum.” “There are no strata anywhere between the 3rd and the 11th c. to accommodate the king’s 9th c. palace. Yet, there is a 2nd/3rd c. Roman period palace in Winchester for which no one claims ownership.” [52] Therefore, according to Heinsohn, the 2nd/3rd c. building stratum belongs to the period of Alfred. This is also consistent with the Roman style of Alfred’s coins (as is the case with Charlemagne’s). Heinsohn’s theory of the contemporaneity of the Early Middle Ages and Roman Antiquity solves the riddle of the legendary King Arthur: “The Celtic ruler Arthur of Camelot, active in a time when Saxons and Romans are simultaneously and competitively at war to conquer England, finds his alter ego in Aththe-Domaros of Camulodunum, the finest Celtic military leader in the period of Emperor Augustus, whose archaeological evidence moves to a stratigraphy-based date of c. 670s-710s AD.” “Camelot, Chrétien de Troyes’ [c. 1140-1190 AD] name for Arthur’s Court, is derived directly from Camelod-unum, the name of Roman Colchester.” [53] Thus both Arthur of Camelot and Aththe of Camulodunum, by reuniting, come out of obscurity. This is a good illustration of the way Heinsohn, rather than extinguishing parts of history, brings them into the light of history. The Vikings of the 8th century were contemporary with the Franks and Saxon invaders: “1st-3rd as well as 4th-6th c. Scandinavians were the same people we call Vikings today. The evidence that stratigraphically belongs only to their 8th-10th c. period has been spread over the entire 1st millennium to fill a 1,000 year time span whose construction is neither understood nor challenged.” [54] “Viking 9th c. longboats with square sails are in actual fact found at the same stratigraphic depth as Roman longboats with square sails. The latter are wrongly dated 700 years too early to the 2nd c. CE. Therefore, the Scandinavians’ supposed 700 year delay in all major fields of development, like towns, ports, breakwaters, kingship, coinage, monotheism, and sailing ships, is derived from chronological ideas that make the Roman period some 700 years older than stratigraphy allows.” [55]

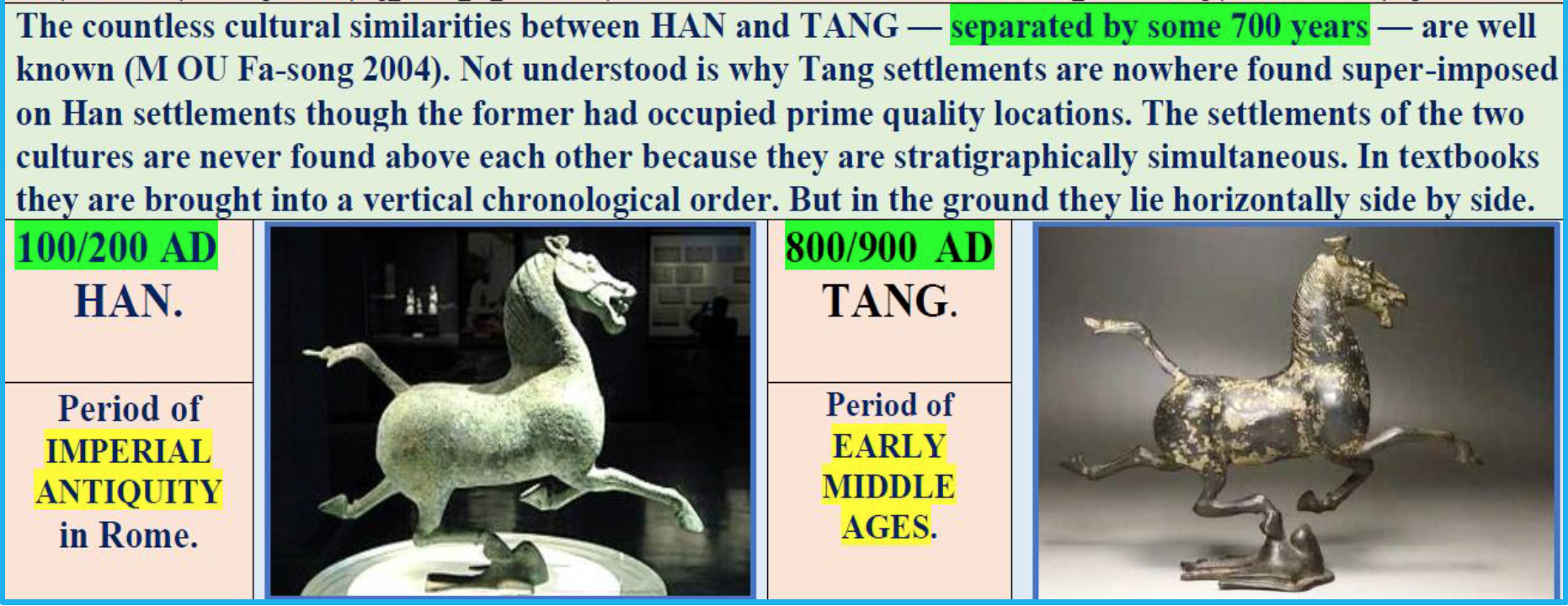

Similar problems are found throughout the lands of Franks, Saxons and Slavs — that is, in the regions where archeological finds are generally dated to the Early Middle Ages. Thus, the cities of Pliska and Preslav in Bulgaria, supposedly built in the 9th century, are entirely consistent with 1st-3rd century Roman architecture and technology. “The eternal controversies between different Bulgarian schools of archaeology about whether Pliska and Preslav belong to Antiquity, Late Antiquity or the Early Middle Ages could never come to a conclusion because all of them are right.” [56]Heinsohn’s shortened chronology of the first millennium solves fundamental inconsistencies in the history of many regions of the globe. It explains, for example, “why the invention of hand-made paper takes about 700 years to spread from China to east and west.” “The enigmatic absence of paper in Japan, so close to China, up to the 8th century AD, when it was suddenly produced in 40 provinces, can be explained, too, by taking into account that the Han stratigraphically are some 700 years younger than in textbook chronology.” [57] Other problems include the fact that Han and Tang art are indistinguishable:

Inconsistencies in the history of Arabs are also solved. “Nobody understands how the inheritors of the Nabataeans and their Aramaic language dominating long distance trade between Asia in the East and the Roman Empire in the West can survive some 700 years without being able to mint coins or sign contracts. This extreme Arab primitivism stands in stark contrast to the Arabs who thrive from the 8th to the beginning of the 10th centuries CE. Their coins are not only found in Poland but from Norway all the way to India and beyond at a time when the rest of the known world was trying to crawl out of the darkness of the Early Middle Ages, and civilization might have been lost for good had not Arabs kept it alive.” [58] On the other hand, “The coin finds of Raqqa, for example, which stratigraphically belongs to the Early Middle Ages (8th-10th century), also contain imperial Roman coins from Imperial Antiquity (1st-3rd century) and Late Antiquity (4th-7th century).” [59]

“The Arabs did not walk in ignorance without coinage and writing for some 700 years. Those 700 years represent phantom centuries. Thus, it is not true that Arabs were backward in comparison with their immediate Roman and Greek neighbours who, interestingly enough, are not on record for having ever claimed any Arab backwardness. In the stratigraphy of ancient sites, Arab coins are found at the same stratigraphic depth as imperial Roman coins from the 1st to the early 3rd c. CE. Thus, the caliphs now dated from the 690s to the 930s are actually the caliphs of the period from Augustus to the 230s. The Romans from Augustus to the 230s knew them as rulers of Arabia Felix. The Romans from the same 1-230s period in its duplication to the 290-530s period (“Late Antiquity”) knew them as Ghassanid caliphs with the same reputation for anti-trinitarian monotheism as the Abbasid Caliphs now dated to 8th/9th centuries.” [60]Heinsohn’s articles contain an abundance of quotes from archeologists puzzled by the contradictions between their hard evidence and their received chronology, yet betray their craft by yielding to chronology. Here is how Israeli archeologist Moshe Hartal is quoted in an Haaretz article: “During the course of a dig designed to facilitate the expansion of the Galei Kinneret Hotel, Hartal noticed a mysterious phenomenon: Alongside a layer of earth from the time of the Umayyad era (638-750[CE]), and at the same depth, the archaeologists found a layer of earth from the Ancient Roman era (37 BCE-132[CE]). ‘I encountered a situation for which I had no explanation — two layers of earth from hundreds of years apart lying side by side,’ says Hartal. ‘I was simply dumbfounded’.” [61]

Roman and Abbasid millefiori bowls that are identical, yet supposedly seven centuries apart

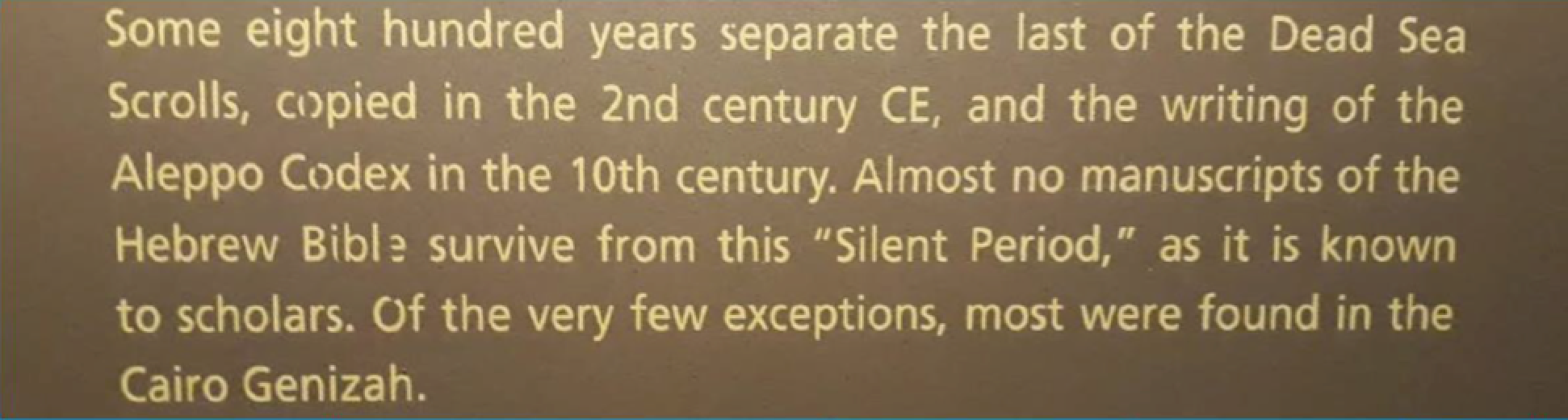

Although Heinsohn has not yet written specifically about first-millennium Israel, he has noted the same gaps in the historical record. As the following signboard photographed in the Israel Museum of Jerusalem puts it: [62]

The Cataclysmic hypothesisHeinsohn links with the cataclysmic paradigm pioneered by Immanuel Velikovsky, a Russian-born scientist, author in 1950 of Worlds in Collision (Macmillan), followed by Ages in Chaos and Earth in Upheaval (Doubleday, 1952 and 1956). Although Velikovsky’s books were then severely attacked by the scientific community, his hypothesis of a major cataclysm caused by the tail of a giant comet about ten thousand years ago has been vindicated. [63] There is a growing consensus that the sudden drop of global temperatures that marked the beginning of the geological era of the Younger Dryas 12,000 years ago started with a comet impact that blew large amounts of dust and ashes into the atmosphere, eclipsing the sun for years. This catastrophic comet and later ones may have formed the basis for the worldwide myths about flying and fire-breathing dragons (read here). For the first millennium AD, Heinsohn gathers evidence of three major civilization collapses caused by cosmic catastrophe followed by plague, in the 230s, the 530s and the 930s, and argues that they are one and the same, described differently in Roman, Byzantine, and Medieval sources. [64]The first of these cataclysms caused the “Crisis of the Third Century” that started in the 230s. Textbook history defines it primarily as “a period in which the Roman Empire nearly collapsed under the combined pressures of barbarian invasions and migrations into the Roman territory, civil wars, peasant rebellions, political instability” ( Wikipedia). Disease played a major role, most notably with the Plague of Cyprian (c. 249-262), originating in Pelusium in Egypt. At the height of the outbreak, 5,000 people were said to be dying every day in Rome (Kyle Harper, The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire, Princeton UP, 2017). Although Latin sources make no mention of it, the massive damage observed by archeologists in several cities suggest that the crisis was triggered by a cosmic cataclysm. In Rome, “Trajan’s market—the commercial heart of the known world—was massively damaged and never repaired again. All eleven aquaeducts were destroyed. The first was not repaired before 1453.” [65] As illustrated above, thick layers of so-called “dark earth” are found immediately above the 3rd century, with no new construction above before the 10th century. This situation, which is repeated in many other Western cities such as London, is generally interpreted as proof that the land was converted to arable and pastoral use or abandoned entirely for seven centuries. But it is more likely that the mud resulted primarily from a cosmic cataclysm. Three hundred years after the Third Century Crisis in Italy, the Eastern Empire was impacted by identical phenomena, whose effect, notes historian of Late Antiquity Wolf Liebeschuetz, “was like the crisis of the third century.” [66] A climatic disaster is documented by ancient historians of that period, such as Procopius of Caesarea, Cassiodorus, or John of Ephesus, who writes: “the sun became dark and its darkness lasted for eighteen months. […] As a result of this inexplicable darkness, the crops were poor and famine struck.” To explain this “miniature ice age,” confirmed relatively by tree-ring and ice-core data, some scientists like David Keys hypothesize massive volcanic irruptions ( Catastrophe: An Investigation into the Origins of the Modern World, Balanine, 1999, and the Channel 4 documentary based on it; read also this article). Others see “a comet impact in AD 536” causing a plunge in temperatures by as much as 5.4 degrees Fahrenheit for several years, leading to the crop failures that brought famine to the Roman Empire. Its weakened inhabitants soon became vulnerable to diseases. In 541, bubonic plague struck the Roman port of Pelusium, exactly like Cyprian’s Plague 300 years earlier, this time spreading to Constantinople, with some 10,000 people dying daily in Justinian’s capital alone, according to Procopius. In the words of John Loeffler, “How Comets Changed the Course of Human History”: “The terrified citizens and merchants fled the city of Constantinople, spreading the disease further into Europe, where it laid waste to communities of famished Europeans as far away as Germany, killing anywhere from a third to a half of the population” [67] (watch also Michael Lachmann’s BBC documentary “The Comet’s Tale”).

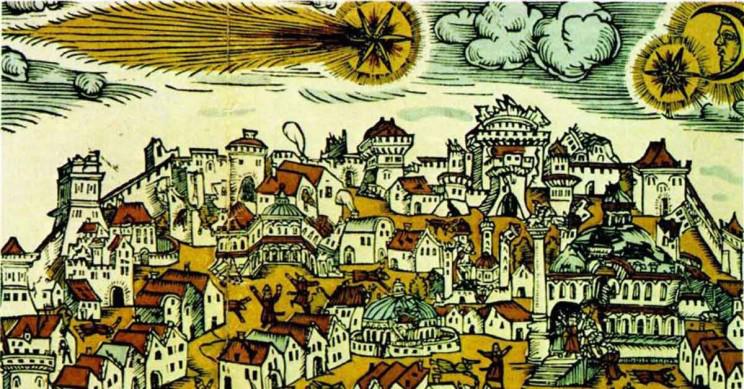

Justinian’s comet over Constantinople

According to Heinsohn, the Western collapse of the third century and the Eastern collapse of the sixth century are both identical with the “Tenth Century Collapse” starting in the 930s. [68] This civilizational collapse is documented by archeology in peripheral parts of the Empire: “Widespread destructions from Scandinavia to Eastern Europe and the Black Sea are dated to the end of the Early Middle Ages (930s CE). The disaster struck in territories where no devastations appear to have occurred during the ‘Crisis of the Third Century’, or the ‘Crisis of the Sixth Century’.” [69] Archeology shows that Austria, Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria were also hit in the early 10th century, as well as Slovak and Czech territories. Bulgarian metropolis Pliska basically disappeared, strangled by a considerable amounts of erosion material (colluvium), also known as “black earth”. All Baltic ports suddenly and mysteriously “undergo discontinuity.” [70]What Heinsohn calls the “Tenth Century Collapse” is well known to historians of the Middle Ages, but generally attributed to invasions. Mark Bloch wrote about it in his classic work Feudal Society (1940): “From the turmoil of the last invasions, the West emerged covered with countless scars. The towns themselves had not been spared — at least not by the Scandinavian — and if many of them, after pillage or evacuation, rose again from their ruins, this break in the regular course of their life left them for long years enfeebled. […] Along the river routes the trading centres had lost all security […] Above all, the cultivated land suffered disastrously, often being reduced to desert. […] Naturally the peasants, more than any other class, were driven to despair by these conditions. […] The lords, who derived their revenues from the land, were impoverished.” [71]

This upheaval marked the end of the ancient world and would be followed by the emergence of the feudal world. Guy Blois, in The Transformation of the Year One Thousand, describes the transition as global and sudden. In some region like the Mâconnais, which he studied in detail, “twenty to twenty-five years sufficed to transform the social landscape from top to bottom.” “There was no gentle progress by imperceptible transitions from one situation to another. There was drastic upheaval, affecting all aspects of social life: a new distribution of power, a new relation of exploitation (the seigneurie), new economic mechanisms (the irruption of the market), and a new social and political ideology. If the word revolution means anything, it could hardly find a better application.”

At the same time, the actual factors and processes of transformation remain largely mysterious, because the 10th century is “a period which is among the most mysterious in our history,” and “has left few traces in our collective memory.” [72] Sources of information from the 10th century are almost non-existent, and the sources from the 11th century not very explicit about the ills of the 10th century. The people of the early 11th century lived with a sense of a radical seizure between the last century, a time of destruction, disintegration, and confusion, and their present, a time full of promises which would soon give birth to what historians call the “Renaissance of the Twelfth Century”. Heinsohn remarks: “The Tenth Century Collapse ran its lethal course closer to the present than any other world-shaking event in human history. However, it is the least researched, too. … We do not yet know what could have been powerful enough to bring about such a mind-boggling transformation of our planet. Though it must have been enormous we still cannot reconstruct the cosmic scenario.” [73] This is because most sources dealing with the catastrophe have been shifted backward. Yet the few Western chronicles that we have for the 11th century do inform us. The monk Rodulfus Glaber, writing between 1026 and 1040, mentions for December of 997, “there appeared in the air an admirable wonder: the form, or perhaps the body itself, of a huge dragon, coming from the north and heading south, with dazzling lightning bolts. This prodigy terrified almost all those who saw it in the Gauls.” Glaber also mentions that, between 993 and 997, “Mount Vesuvius (which is also called Vulcan’s Caldron) gaped far more often than his wont and belched forth a multitude of vast stones mingled with sulphurous flames which fell even to a distance of three miles around. […] It befell meanwhile that almost all the cities of Italy and Gaul were ravaged by flames of fire, and that the greater part even of the city of Rome was devoured by a conflagration. […] At this same time a horrible plague raged among men, namely a hidden fire which, upon whatsoever limb it toned, consumed it and severed it from the body. […] Moreover, about the same time[997], a most mighty famine raged for five years throughout the Roman world [ in universo Romano orbe], so that no region could be heard of which was not hunger stricken for lack of bread, and many of the people were starved to death. In those days also, in many regions, the terrible famine compelled men to make their food not only of unclean beasts and creeping things, but even of men’s, women’s, and children’s flesh, without regard even of kindred; for so fierce waxed this hunger that grown-up sons devoured their mothers, and mothers, forgetting their maternal love ate their babes.” [74]

The birth of AD chronologyIn Phantoms of Remembrance: Memory and Oblivion at the End of the First Millennium, Patrick Geary writes, referring to the Tenth Century Collapse: “Those living on the other side of this caesura felt themselves separated by a great gulf from this earlier age. Already in the eleventh century those people who undertook to preserve the past in written form, for their contemporaries or their posterity, seemed to know little and understand less of their familial, institutional, cultural, and regional past. […] And yet they were deeply concerned with this past, possessed by it almost, and their invented past became the goal and justification of their programs in the present.” [75]

From the “Ground Zero” of the Tenth Century Collapse, they recreated this past from bits and pieces — a form of “recovered memory”. It is this recreation that we have: “Much of what we think we know about the early Middle Ages was determined by the changing problems and concerns of eleventh-century men and women, not by those of the more distant past. Unless we understand the mental and social structures that acted as filters, suppressing or transforming the received past in the eleventh century in terms of presentist needs, we are doomed to misunderstand those earlier centuries.” [76]

The confused perspective of eleventh-century men on earlier ages can account for the chronological distortions that later made it into history books. Within a few generations, what Rodulfus Glaber still calls “the Roman world” (citation above), destroyed by cataclysms, plague and famine only decades before his time, was idealized and pushed back in almost mythical times. This coincides with the rise of Christianity, heavily dominated by apocalypticism in its infancy. In Matthew 24:6-8, when Jesus’ disciples asked him: “Tell us, when is this going to happen, and what sign will there be of your coming ( parousia) and of the end of the world?” he answered: “There will be famines and earthquakes in various places. All this is only the beginning of the birthpangs.” [77] “In the minds of survivors,” Heinsohn writes, “the ancient gods had failed, but the apocalyptic books of the Bible had been proven right. Spontaneous conversions to the various Judaism-derived sects quickly increased throughout the empire.” [78] The Book of Revelation sounded like a summary of the conflagrations just passed: “A mighty earthquake took place, and the sun became black like animal hair sack-cloth, and the full moon became like blood, and the stars of heaven fell to the earth, […] And the kings of the earth, and the great people and the generals and the rich and the powerful, and everyone, slave and free, hid themselves in the caves, and among the rocks of the mountains. […] There came hail and fire mixed with blood, and it was rained on the earth. And one third of the earth was burned up, and one third of the trees were burned up, and all the green grass was burned up. Something like a huge mountain burning with fire was hurled into the sea. […] A huge star fell from heaven, burning like a lamp, and it fell on a third of the rivers, and on the sources of the waters.” (from Revelation of John, chapters 6 and 8)

Heinsohn suggests that the Book of Revelation directly influenced the chronological shift, because its chapter 20 postulates a thousand period between Jesus and the catastrophe: “Then I saw an angel coming down from heaven. / He took hold of the dragon, / Satan, and chained him for 1,000 years. / He could not fool the nations anymore until the 1,000 years were completed.” Church father Cyprianus (200-258 AD, i.e. 900-958 in revised chronology), a survivor of the catastrophe in his heavily hit city of Carthage, wrote: “Our Lord has foretold all this. War and famine, earth quakes and pestilence will occur everywhere” ( On Mortality). [79] Rodulfus Glaber also wrote at the end of book 2: “All this accords with the prophecy of St John [Revelation 20:7], who said that the Devil would be freed after a thousand years.” Heinsohn suggests Michael Psellos (c. 1018-1078 AD), author of the Chronographia, as the main engineer of the chronological shift. [80]To understand more precisely the role played by Christianity in the chronological reset, we would need a clear vision of the history of early Christianity, which we don’t have, as I have shown in Part 2. What is almost certain is that, contrary to what Church historians have written, the Roman world was not dominated by Christianity until the eleventh-century Gregorian Reform. Excavation of Carolingian tombs casts doubt on the Christian religion of that age: “excavators recently analyzing the contents of 96 Carolingian burials from 86 different locations (dated 751-911, but mostly from the time of Charlemagne and Louis the Pious), were shocked by an extremely widespread practice resembling Charon’s obol. That payment was used as a means of bribing the legendary ferryman for passage across the Styx, the river that divided the world of the living from the world of the dead.” [81] Even more puzzling — but logical within the Heinsohnian paradigm —, some of those coins are Roman coins. One likely factor in the chronological confusion of the eleventh century, leading to the stretch of 300 years into a millennium, came from the traditional Roman computation. Roman historians counted years ab urbe condita (“since the foundation of the city”), abbreviated AUC. A monk named Dionysius Exiguus determined that Jesus’ birth took place in 753 AUC. That means that 1000 AUC falls on 246 AD, during the Third Century Crisis. People living soon after the cataclysm (like Dionysius) [82] believed they were living around 1000 AUC. They could easily be led to believe that they really lived 1000 years after Christ. It has actually been suggested that the “Dominus” in Anno Domine originally meant Romulus, the founder of Rome. Changing Romulus into Christ would have been easy since both legendary figures have similar mythical attributes. Like Christ, Romulus suffered a sacrificial death, and then the Romans “began to cheer Romulus, like a god born of a god, the king and the father of the city, imploring his protection, so that he should always protect his children with his benevolent favor” (Titus Livy, History of Rome I.16). (Whether we take the resemblance between Romulus and Christ as another clue that Livy is a medieval or Renaissance fabrication makes little difference.) At some stage, people were led by the Church to change their notion of living one millennium after Romulus into the notion of living one millennium after Christ. This shift was part and parcel of the Christianization process: just like the Church Christianized many Pagan gods, holy places and holy days, it Christianized AUD into AD. The confusion was facilitated by the fact that AUC was still used in the eleventh century (some chroniclers such as Ademar of Chabannes also counted years in annus mundi, based on biblical chronology). Since, according to Dionysius, Jesus was born in 753 AUC, the confusion of AUC with AD added 753 years, which is approximately the length of phantom time added into the first millennium according to Heinsohn. The Church was then too happy to fill in the vacuum and make itself look older than it was, with forgeries such as Liver Pontificalis, the Donation of Constantine, and the pseudo-Isidorian decretals. Papal clerics imposed their millennium-long Christian history, when in reality, their Christ had been crucified (under Augustus) only 300 years before Gregory VII (1073-1085). In the comment section of my previous installment, Professor Eric Knibbs has objected to the theory that the AD chronology was imposed after the Tenth Century Collapse, by the Gregorian reformers or their immediate predecessors. He has provided evidence that AD dates were already in use in ninth-century manuscripts. For instance, on codex Sankt-Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek 272 ( here page 245), we read “ anno dccc.vi. ab incarnatione domini” (“In the year 806 from the incarnation of the Lord”). In Ms. lat. 2341, Paris, Bibl. nat. ( here), future dates for the celebration of Easter are given in the form “anno incarnationis domini nostri iesu christi dcccxliii” (“the year of the incarnation of our lord Jesus Christ 843”). Another case is Clm 14429 at the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek ( here), which indicates on the first folio the date when it was copied: “ anno domini dcccxxi” (“the year of the Lord 821”). However, on second thought, I find the objection inconclusive, because there is no way of knowing if scribes were using AD dates consistently. The problem is illustrated by the above-mentioned Rodulfus Glaber, writing between 1026 and 1040. In Book II, §8 of his autograph manuscript, Rodulfus gives the date “888 of the Word incarnate” instead of 988 (according to the editor’s footnote in my Latin-French edition). In Book 1, §23, he mentions an event during the pontificate of Benedict VIII (1012-1024) and dates it from “the year 710 of the Lord’s incarnation.” The editor corrects him in footnote: “In fact in 1014, but the manuscript corrected by Rodulfus carries indisputably the date 710; nothing explains such a mistake.” [83] One thing that can explain such mistakes is the floating state of the chronology. Most probably, Rodulfus borrowed these “erroneous” dates from others without realizing they were tuned on a different dating scale. Even a manuscript carrying a date like 806 AD could be misdated, that is, written by someone counting years with a shorter chronology and living in the Gregorian age. What is illustrated by Rodulfus is that the AD dating system did not become settled overnight, and that different people could ascribe different AD dates to very recent times. A case by case examination of supposedly ninth-century manuscripts with AD dates should determine if the dating is consistent with these manuscripts surviving the Tenth Century Collapse. Starting from the premise that AD dates were well established long before the Gregorian Reform, historians have assumed that, when medieval men saw the year 1000 approach, they must have feared the worst. This assumption has been proven false: our sources are mute about the supposed “fears of the year 1000.” Historians who nevertheless insist on its reality, like Richard Landes, resort to funny arguments like “a consensus of silence that masks a great deal of concern. […] medieval writers avoided the subject of the millennium whenever and wherever possible.” [84] More convincingly, the missing “fears of the year 1000” make a strong argument that the AD computation came in use after the year 1000. In the two previous installments, I pointed out all kinds of reasons to question the authenticity and accepted dating of many sources. Some of my working hypotheses can now be corrected. In Part 1, “How fake is Roman Antiquity?” I agreed with Polydor Hochart’s objection to the possibility that books from Imperial Rome were preserved until the 14th-15th century because monks copied them in the 9th, 10th or 11th century. Christian monks copying Pagan works on expensive parchments is just not credible. Rather, we have every reason to believe that, whenever they got their hands on such books, monks either destroyed them or scrapped them to reuse the parchment. Hochart therefore concludes that these books from Imperial Rome are forgeries. But Heinsohn’s revised chronology now gives us a more satisfactory solution: the original composition of these works (1st century) and their medieval copies (9th century at the earliest) are not separated by seven centuries or more, but by one or two centuries at the most. The 9th century still belonged to Roman times, and Christianity was then in its infancy. That doesn’t eliminate suspicion of Medieval or Renaissance fraud, but that reduces it. We can now read Roman sources with a different perspective. In Part 2, “How fake is Church history?”, I focused on Church history and agreed with Jean Hardouin (1646-1729), the Jesuit librarian who came to the frightening conclusion that all the works ascribed to Augustine (AD 354-430), Jerome of Stridon (AD 347-420), Ambrose of Milan (c. AD 340-397), ad many others, could not have been written before the 11th or 12th century, and were therefore forgeries. We can now consider that Hardouin was both right and wrong. He was right in estimating these works much younger than officially claimed (though perhaps wih some exaggeration), but he was not necessarily right in concluding that they were forgeries; if Augustine, Jerome and Ambrose really belong, in stratigraphic time, to the end of the Early Middle Ages at the earliest, it is no wonder they are attacking the same heresies as the medieval Church who promoted them. Notes [1] Nicolas Standaert, “Jesuit Accounts of Chinese History and Chronology and Their Chinese Sources,” East Asian Science, Technology, and Medicine, no. 35, 2012, pp. 11–87, on www.jstor.org [2] Anatoly Fomenko and Gleb Nosovsky, History: Fiction or Science, volume 1: Introducing the problem. A criticism of the Scaligerian chronology. Dating methods as offered by mathematical statistics. Eclipses and zodiacs,ch. 6, p. 356. [3] Anatoly Fomenko and Gleb Nosovsky, History: Fiction or Science, vol. 2: The dynastic parallelism method. Rome. Troy. Greece. The Bible. Chronological shifts ( archive.org) pp. 19-42. [15] From Heinsohn’s letter to Eric Knibbs, 2020, communicated to the author.

[25] Theodor Mommsen, A History of Rome Under the Emperors. Routledge, 2005, p. 281. [31] Michael J. Decker, The Byzantine Dark Ages, Bloomsbury Academic, 2016; Eleonora Kountoura-Galake, ed., The Dark Centuries of Byzantium (7th-9th C.), National Hellenic Research Foundation, 2001. [44] From Heinsohn’s letter to Eric Knibbs, 2020, communicated to the author. [63] Velikovsky hypothesized that the comet settled as planet Venus. It has been recently reported ( here) that “Venus sports a giant, ion-packed tail that stretches almost far enough to tickle the Earth when the two planets are in line with the Sun.” Read also “When a planet behaves like a comet”. Velikovsky is given due credit by astronomer James McCanney, author of Planet-X, Comets & Earth Changes: A Scientific Treatise on the Effects of a New Large Planet or Comet Arriving in our Solar System and Expected Earth Weather and Earth Changes, jmccanneyscience.com press, 2007 (read here). [67] John Loeffler, “How Comets Changed the Course of Human History,” November 30th, 2008, on interestingengineering.com/how-comets-changed-the-course-of-human-history [68] Useful article: Declan M Mills, “The Tenth-Century Collapse in West Francia and the Birth of Christian Holy War,” Newcastle University Postgraduate Forum E-Journal, Edition 12, 2015, online here. [71] Mark Bloch, Feudal Society (1940), Routledge, 2014, pp. 43-44. [72] Guy Blois, The Transformation of the Year One Thousand: The Village of Lournand from autiquity to feudalism, Manchester UP, 1992, pp. 161, 167, 1. [74] Raoul Glaber, Histoires, ed. and trans. Mathieu Arnoux, Brépols, 1996, book II, § 13-17, pp. 116-125.

[75] Patrick J. Geary, Phantoms of Remembrance: Memory and Oblivion at the End of the First Millenium, Princeton UP, 1994, p. 9. [76] Patrick J. Geary, Phantoms of Remembrance: Memory and Oblivion at the End of the First Millenium, Princeton UP, 1994, p. 7. [77] Edward Adams, The Stars Will Fall From Heaven: ‘Cosmic Catastrophe’ in the New Testament and its World, The Library of New Testament Studies, 2007. [82] Dionysius supposedly made his computation in 532 AD, but since he was living in Bulgaria, in the Byzantine world, this date corresponds to 232 in Imperial Antiquity (and to 932 AD in Early Middle Ages). [83] Raoul Glaber, Histoires, ed. and trans. Mathieu Arnoux, Brépols, 1996, pp. 106-107 and 78-79. [84] Richard Landes, “The Fear of an Apocalyptic Year 1000: Augustinian Historiography, Medieval and Modern,” Speculum, Vol. 75, No. 1 (Jan., 2000), pp. 97-145, on www.jstor.org

|