This is the first of a series of three articles challenging the conventional historical framework of the Mediterranean world from the Roman Empire to the Crusades. It is a collective contribution to an old debate that has gained new momentum in recent decades in the fringe of the academic world, mostly in Germany, Russia, and France. Some working hypotheses will be made along the way, and the final article will suggest a global solution in the form of a paradigm shift based on hard archeological evidence.

Tacitus and BraccioliniOne of our most detailed historical sources on imperial Rome is Cornelius Tacitus (56-120 CE), whose major works, the Annals and the Histories, span the history of the Roman Empire from the death of Augustus in 14 AD, to the death of Domitian in 96.

Here is how the French scholar Polydor Hochart introduced in 1890 the result of his investigation on “the authenticity of the Annals and the Histories of Tacitus,” building up on the work of John Wilson Ross published twelve years earlier, Tacitus and Bracciolini: The Annals forged in the XVth century (1878):

“At the beginning of the fifteenth century scholars had at their disposal no part of the works of Tacitus; they were supposed to be lost. It was around 1429 that Poggio Bracciolini and Niccoli of Florence brought to light a manuscript that contained the last six books of the

Annals and the first five books of the

Histories. It is this archetypal manuscript that served to make the copies that were in circulation until the use of printing. Now, when one wants to know where and how it came into their possession, one is surprised to find that they have given unacceptable explanations on this subject, that they either did not want or could not say the truth. About eighty years later, Pope Leo X was given a volume containing the first five books of the

Annals. Its origin is also surrounded by darkness. / Why these mysteries? What confidence do those who exhibited these documents deserve? What guarantees do we have of their authenticity? / In considering these questions we shall first see that Poggio and Niccoli were not distinguished by honesty and loyalty, and that the search for ancient manuscripts was for them an industry, a means of acquiring money. / We will also notice that Poggio was one of the most learned men of his time, that he was also a clever calligrapher, and that he even had in his pay scribes trained by him to write on parchment in a remarkable way in Lombard and Carolin characters. Volumes coming out of his hands could thus imitate perfectly the ancient manuscripts, as he says himself. / We will also be able to see with what elements the

Annals and the

Histories were composed. Finally, in seeking who may have been the author of this literary fraud, we shall be led to think that, in all probability, the pseudo-Tacitus is none other than Poggio Bracciolini himself.”

[1]

Hochart’s demonstration proceeds in two stages. First, he traces the origin of the manuscript discovered by Poggio and Niccoli, using Poggio’s correspondence as evidence of deception. Then Hochart deals with the emergence of the second manuscript, two years after Pope Leo X (a Medici) had promised great reward in gold to anyone who could provide him with unknown manuscripts of the ancient Greeks or Romans. Leo rewarded his unknown provider with 500 golden crowns, a fortune at that time, and immediately ordered the printing of the precious manuscript. Hochart concludes that the manuscript must have been supplied indirectly to Leo X by Jean-François Bracciolini, the son and sole inheritor of Poggio’s private library and papers, who happened to be secretary of Leo X at that time, and who used an anonymous intermediary in order to elude suspicion.

Both manuscripts are now preserved in Florence, so their age can be scientifically established, can’t it? That is questionable, but the truth, anyway, is that their age is simply assumed. For other works of Tacitus, such as

Germania and

De Agricola, we don’t even have any medieval manuscripts. David Schaps tells us that

Germania was ignored throughout the Middle Ages but survived in a single manuscript that was found in Hersfeld Abbey in 1425, was brought to Italy and examined by Enea Silvio Piccolomini, later Pope Pius II, as well as by Bracciolini, then vanished from sight.

[2]Poggio Bracciolini (1380-1459) is credited for “rediscovering and recovering a great number of classical Latin manuscripts, mostly decaying and forgotten in German, Swiss, and French monastic libraries” (

Wikipedia). Hochart believes that Tacitus’ books are not his only forgeries. Under suspicion come other works by Cicero, Lucretius, Vitruvius, and Quintilian, to name just a few. For instance, Lucretius’ only known work,

De rerum natura “virtually disappeared during the Middle Ages, but was rediscovered in 1417 in a monastery in Germany by Poggio Bracciolini” (

Wikipedia). So was Quintilian’s only extant work, a twelve-volume textbook on rhetoric entitled

Institutio Oratoria, whose discovery Poggio recounts in a

letter:

“There amid a tremendous quantity of books which it would take too long to describe, we found Quintilian still safe and sound, though filthy with mould and dust. For these books were not in the library, as befitted their worth, but in a sort of foul and gloomy dungeon at the bottom of one of the towers, where not even men convicted of a capital offence would have been stuck away.”

Provided Hochart is right, was Poggio the exception that confirms the rule of honesty among the humanists to whom humankind is indebted for “rediscovering” the great classics? Hardly, as we shall see. Even the great Erasmus (1465-1536) succumbed to the temptation of forging a treatise under the name of saint Cyprian (

De duplici martyrio ad Fortunatum), which he pretended to have found by chance in an ancient library. Erasmus used this stratagem to voice his criticism of the Catholic confusion between virtue and suffering. In this case, heterodoxy gave the forger away. But how many forgeries went undetected for lack of originality? Giles Constable writes in “Forgery and Plagiarism in the Middle Ages”: “The secret of successful forgers and plagiarists is to attune the deceit so closely to the desires and standards of their age that it is not detected, or even suspected, at the time of creation.” In other words: “Forgeries and plagiarisms … follow rather than create fashion and can without paradox be considered among the most authentic products of their time.”

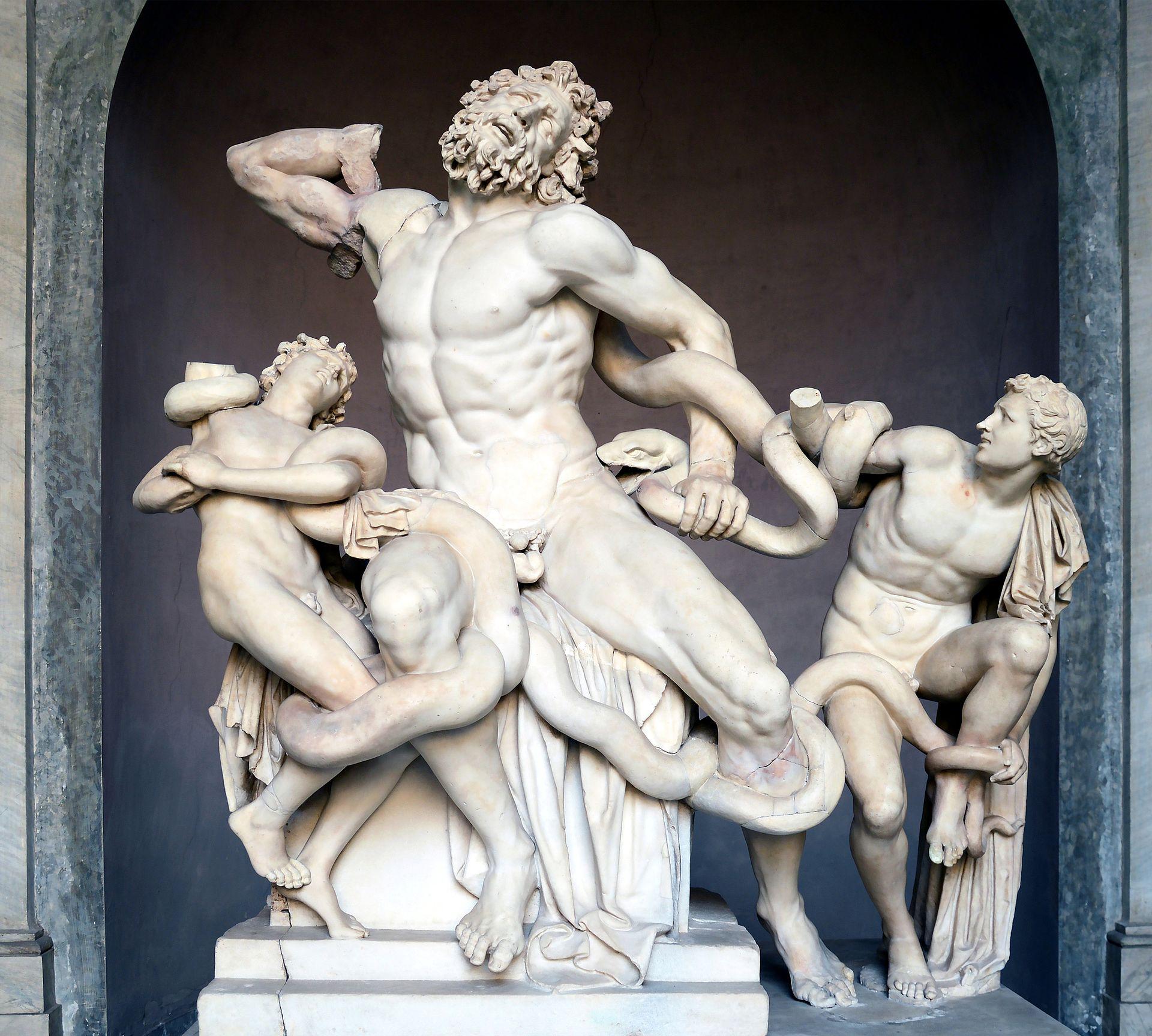

[3]We are here focusing on literary forgeries, but there were other kinds. Michelangelo himself launched his own career by faking antique statues, including one known as the

Sleeping Cupid (now lost), while under the employment of the Medici family in Florence. He used acidic earth to make the statue look antique. It was sold through a dealer to Cardinal Riario of San Giorgio, who eventually found out the hoax and demanded his money back, but didn’t press any charges against the artist. Apart from this recognized forgery, Lynn Catterson has made a strong case that the sculptural group of “Laocoon and his Sons,” dated from around 40 BC and supposedly discovered in 1506 in a vineyard in Rome and immediately acquired by Pope Julius II, is another of Michelangelo’s forgery (read

here)

[4].

When one comes to think about it seriously, one can find several reasons to doubt that such masterworks were possible any time before the Renaissance, one of them having to do with the progress in human anatomy. Many other antique works raise similar questions. For instance, a comparison between Marcus Aurelius’ bronze equestrian statue (formely thought to be Constantine’s), with, say, Louis XIV’s, makes you wonder: how come nothing remotely approaching this level of achievement can be found between the fifth and the fifteenth century?

[5] Can we even be sure that Marcus Aurelius is a historical figure? “The major sources depicting the life and rule of Marcus are patchy and frequently unreliable” (

Wikipedia), the most important one being the highly dubious

Historia Augusta (more later).

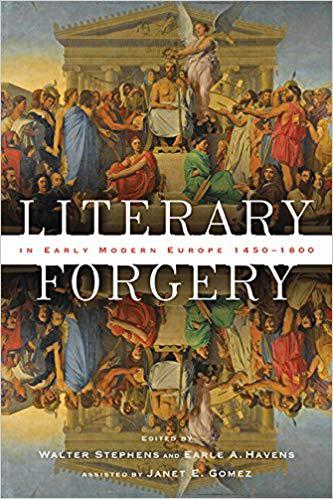

The lucrative market of literary forgeries“Literary Forgery in Early Modern Europe, 1450-1800” was the subject of a 2012 conference, whose proceedings were published in 2018 by the John Hopkins University Press (who also published a 440-page catalog,

Bibliotheca Fictiva: A Collection of Books & Manuscripts Relating to Literary Forgery, 400 BC-AD 2000). One forger discussed in that book is

Annius of Viterbo (1432-1502), who produced a collection of eleven texts, attributed to a Chaldean, an Egyptian, a Persian, and several ancient Greeks and Romans, purporting to show that his native town of Viterbo had been an important center of culture during the Etruscan period. Annius attributed his texts to recognizable ancient authors whose genuine works had conveniently perished, and he went on producing voluminous commentaries on his own forgeries.

This case illustrates the combination of political and mercantile motives in many literary forgeries. History-writing is a political act, and in the fifteenth century, it played a crucial role in the competition for prestige between Italian cities. Tacitus’ history of Rome was brought forward by Bracciolini thirty years after a Florentine chancellor by the name of Leonardo Bruni (1369-1444) wrote his

History of the Florentine people (

Historiae Florentini populi) in 12 volumes (by plagiarizing Byzantine chronicles). Political value translated into economic value, and the market for ancient works reached astronomical prices: it is said that with the sale of just a copy of a manuscript of Titus Livy, Bracciolini bought himself a villa in Florence. During the Renaissance, “the acquisition of classical artifacts had simply become the new fad, the new way of displaying power and status. Instead of collecting the bones and body parts of saints, towns and wealthy rulers now collected fragments of the ancient world. And just as with the relic trade, demand far outstripped supply” (from the website of San Diego’s

“Museum of Hoaxes”).

In the mainstream of classical studies, ancient texts are assumed to be authentic if they are not proven forged. Cicero’s

De Consolatione is now universally considered the work of

Carolus Sigonius (1520-1584), an Italian humanist born in Modena, only because we have a letter by Sigonius himself admitting the forgery. But short of such a confession, or of some blatant anachronism, historians and classical scholars will simply ignore the possibility of fraud. They would never, for example, suspect Francesco Petrarca, known as Petrarch (1304-1374), of faking his discovery of Cicero’s letters, even though he went on publishing his own letters in perfect Ciceronian style. Jerry Brotton is not being ironic when he writes in

The Renaissance Bazaar: “Cicero was crucial to Petrarch and the subsequent development of humanism because he offered a new way of thinking about how the cultured individual united the philosophical and contemplative side of life with its more active and public dimension. […] This was the blueprint for Petrarch’s humanism.”

[6]The medieval manuscripts found by Petrarch are long lost, so what evidence do we have of their authenticity, besides Petrarch’s reputation? Imagine if historians seriously questioned the authenticity of some of our most cherished classical treasures. How many of them would pass the test? If Hochart is right and Tacitus is removed from the list of reliable sources, the whole historical edifice of the Roman Empire suffers from a major structural failure, but what if other pillars of ancient historiography crumble under similar scrutiny? What about Titus Livy, author a century earlier than Tacitus of a monumental history of Rome in 142 verbose volumes, starting with the foundation of Rome in 753 BC through the reign of Augustus. It is admitted, since Louis de Beaufort’s critical analysis (1738), that the first five centuries of Livy’s history are a web of fiction.

[7] But can we trust the rest of it? It was also Petrarch, Brotton informs us, who “began piecing together texts like Livy’s

History of Rome, collating different manuscript fragments, correcting corruptions in the language, and imitating its style in writing a more linguistically fluent and rhetorically persuasive form of Latin.”

[8] None of the manuscripts used by Petrarch are available anymore.

What about the

Augustan History (

Historia Augusta), a Roman chronicle that Edward Gibbon trusted entirely for writing his

Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire? It has since been exposed as the work of an impostor who has masked his fraud by inventing sources from scratch. However, for some vague reason, it is assumed that the forger lived in the fifth century, which is supposed to make his forgery worthwhile anyway. In reality, some of its stories sound like cryptic satire of Renaissance mores, others like Christian calumny of pre-Christian religion. How likely is it, for example, that the hero Antinous, worshipped throughout the Mediterranean Basin as an avatar of Osiris, was the gay lover (

eromenos) of Hadrian, as told in

Augustan History? Such questions of plausibility are simply ignored by professional historians.

[9] But they jump to the face of any lay reader unimpressed by scholarly consensus. For instance, just reading the summary of Suetonius’

Lives of the Twelve Cesars on the

Wikipedia page should suffice to raise very strong suspicions, not only of fraud, but of mockery, for we are obviously dealing here with biographies of great imagination, but of no historical value whatsoever.

Works of fiction also come under suspicion. We owe the complete version of

The Satyricon, supposedly written under Nero, to a manuscript discovered by Poggio Bracciolini in Cologne.

[10] Apuleius’ novel

The Golden Ass was also found by Poggio in the same manuscript as the fragments of Tacitus’

Annales and

Histories. It was unknown before the thirteenth century, and its central piece, the tale of Cupid and Psyche, seems derived from the more archaic version found in the twelfth-century

Roman de Partonopeu de Blois.[11]The question can be raised of why Romans would bother writing and copying such works on papyrus volumen, but the more important question is: Why would medieval monks copy and preserve them on expensive parchments? This question applies to all pagan authors, for none of them reached the Renaissance in manuscripts allegedly older than the ninth century. “Did the monks, out of pure scientific interest, have a duty to preserve for posterity, for the greater glory of paganism, the masterpieces of antiquity?” asks Hochart.

And not only masterpieces, but bundles of letters! In the early years of the sixteenth century, the Veronian Fra Giovanni Giocondo discovered a volume of 121 letters exchanged between Pliny the Younger (friend of Tacitus) and Emperor Trajan around the year 112. This “book”, writes Latinist scholar Jacques Heurgon, “had disappeared during the whole Middle Ages, and one could believe it definitively lost, when it suddenly emerged, in the very first years of the sixteenth century, in a single manuscript which, having been copied, partially, then completely, was lost again.”

[12] Such unsuspecting presentation is illustrative of the blind confidence of classical scholars in their Latin sources, unknown in the Middle Ages and magically appearing from nowhere in the Renaissance.

The strangest thing, Hochart remarks, is that Christian monks are supposed to have copied thousands of pagan volumes on expensive parchment, only to treat them as worthless rubbish:

“To explain how many works of Latin authors had remained unknown to scholars of previous centuries and were uncovered by Renaissance scholars, it was said that monks had generally relegated to the attics or cellars of their convents most of the pagan writings that had been in their libraries. It was therefore among the discarded objects, sometimes among the rubbish, when they were allowed to search there, that the finders of manuscripts found, they claimed, the masterpieces of antiquity.”

In medieval convents, manuscript copying was a commercial craft, and focused exclusively on religious books such as psalters, gospels, missals, catechisms, and saints’ legends. They were mostly copied on papyrus. Parchment and vellum were reserved for luxury books, and since it was a very expensive material, it was common practice to scrape old scrolls in order to reuse them. Pagan works were the first to disappear. In fact, their destruction, rather than their preservation, was considered a holy deed, as hagiographers abundantly illustrate in their saints’ lives.

How real is Julius Caesar?Independently of Hochart, and on the basis of philological considerations, Robert Baldauf, professor at the university of Basle, argued that many of the most famous ancient Latin and Greek works are of late medieval origin (Historie und Kritik, 1902). “Our Romans and Greeks have been Italian humanists,” he says. They have given us a whole fantasy world of Antiquity that “has rooted itself in our perception to such an extent that no positivist criticisms can make humanity doubt its veracity.”

Baldauf points out, for example, German and Italian influences in Horace’s Latin. On similar grounds, he concludes that Julius Cesar’s books, so appreciated for their exquisite Latin, are late medieval forgeries. Recent historians of Gaul, now informed by archeology, are actually puzzled by Cesar’s

Commentarii de Bello Gallico—our only source on the elusive Vercingetorix. Everything in there that doesn’t come from book XXIII of Poseidonios’

Histories appears either wrong or unreliable in terms of geography, demography, anthropology, and religion.

[13]A great mystery hangs over the supposed author himself. We are taught that “Caesar” was a cognomen (nickname) of unknown meaning and origin, and that it was adopted immediately after Julius Caesar’s death as imperial title; we are asked to believe, in other words, that the emperors all called themselves Caesar in memory of that general and dictator who was not even emperor, and that the term gained such prestige that it went on to be adopted by Russian “Czars” and German “Kaisers”. But that etymology has long been challenged by those (including Voltaire) who claim that Caesar comes from an Indo-European root word meaning “king”, which also gave the Persian Khosro. These two origins cannot both be true, and the second seems well grounded.

Cesar’s gentilice (surname) Iulius does not ease our perplexity. We are

told by Virgil that it goes back to Cesar’s supposed ancestor Iulus or Iule. But Virgil also tells us (drawing from Cato the Elder, c. 168 BC) that it is the short name of Jupiter (

Jul Pater). And it happens to be an Indo-European root word designating the sunlight or the day sky, identical to the Scandinavian name for the solar god,

Yule (

Helios for the Greeks,

Haul for the Gauls,

Hel for the Germans, from which derives the French Noël,

Novo Hel). Is “Julius Caesar” the “Sun King”?

Consider, in addition, that: 1. Roman emperors were traditionally declared adoptive sons of the sun-god Jupiter or of the “Undefeated Sun” (

Sol Invictus). 2. The first emperor, Octavian Augustus, was allegedly the adoptive son of Julius Caesar, whom he divinized under the name Iulius Caesar Divus (celebrated on January 1), while renaming in his honor the first month of summer, July. If Augustus is both the adoptive son of the divine Sun and the adoptive son of the divine Julius, and if in addition Julius or Julus is the divine name of the Sun, it means that the divine Julius is none other than the divine Sun (and the so-called “Julian” calendar simply meant the “solar” calendar). Julius Caesar has been brought down from heaven to earth, transposed from mythology to history. That is a common process in Roman history, according to Georges Dumézil, who explains the notorious poverty of Roman mythology by the fact that it “was radically destroyed at the level of theology [but] flourished in the form of history,” which is to say that Roman history is a literary fiction built on mythical structures.

[14]The mystery surrounding Julius Caesar is of course of great consequence, since on him rests the historiography of Imperial Rome. If Julius Caesar is a fiction, then so is much of Imperial Rome. Note that, on the coins attributed to his era, the first emperor is simply named Augustus Caesar, which is not a name, but a title that could be applied to any emperor.

At this point, most readers will have lost patience. With those whose curiosity surpasses their skepticism, we shall now argue that Imperial Rome is actually, for a large part, a fictitious mirror image of Constantinople, a fantasy that started emerging in the eleventh century in the context of the cultural war waged by the papacy against the Byzantine empire, and solidified in the fifteenth century, in the context of the plunder of Byzantine culture that is known as the Renaissance. This, of course, will raise many objections, some of which will be addressed here, others in further articles.

First objection: Wasn’t Constantinople founded by a Roman emperor, namely Constantine the Great? So it is said. But then, how real is this legendary Constantine?

How real is Constantine the Great?If Julius Caesar is the alpha of the Western Roman Empire, Constantine is the omega. One major difference between them is the nature of our sources. For Constantine’s biography, we are totally dependent on Christian authors, beginning with Eusebius of Caesarea, whose Life of Constantine, including the story of the emperor’s conversion to Christianity, is a mixture of eulogy and hagiography.

The common notion derived from Eusebius is that Constantine moved the capital of his Empire from Rome to Byzantium, which he renamed in his own honor. But that general narrative of the first translatio imperii is itself replete with inner contradictions. First, Constantine didn’t really move his capital to the East, because he was himself from the East. He was born in Naissus (today Nis in Serbia), in the region then called Moesia, West of Thracia. According to standard history, Constantine had never set foot in Rome before he marched on the city and conquered it from Maxentius.

Constantine wasn’t just a Roman who happened to be born in Moesia. His father Constantius also came from Moesia. And so did his predecessor Diocletian, who was born in Moesia, built his palace there (Split, today in Croatia), and died there. In Byzantine chronicles, Diocletian is given as

Dux Moesiae (

Wikipedia), which can mean “king of Moesia”, for well into the Early Middle Ages,

dux was more or less synonymous with

rex.[15]Textbook history tells us that, on becoming emperor, Diocletian decided to share his power with Maximian as co-emperor. That is already odd enough. But instead of keeping for himself the historical heart of the empire, he left it to his subordinate and settled in the East. Seven years later, he divided the Empire further into a

tetrarchy; instead of one Augustus Caesar, there was now two Augustus and two Caesars. Diocletian retired to the far eastern part of Asia Minor, bordering on Persia. Like Constantine after him, Diocletian never reigned in Rome; he visited it once in his lifetime.

This leads us to the second inner contradiction of the

translatio imperii paradigm: Constantine didn’t really move the imperial capital from Rome to Byzantium, because Rome had ceased to be the imperial capital in 286, being replaced by Milan. By the time of Diocletian and Constantine, the whole of Italy had actually fallen into anarchy during the

Crisis of the Third Century (AD 235–284). When in 402 AD, the Eastern emperor Honorius restored order in the Peninsula, he transferred its capital to Ravenna on the Adriatic coast. So from 286 on, we are supposed to have a Roman Empire with a deserted Rome.

The conundrum only thickens when we compare Roman and Byzantine cultures. According to the translatio imperii paradigm, the Eastern Roman Empire is the continuation of the Western Roman Empire. But Byzantium scholars insist on the great differences between the Greek-speaking Byzantine civilization and the earlier civilization of the Latium. Byzantinist Anthony Kaldellis wrote:

“The Byzantines were not a warlike people. […] They preferred to pay their enemies either to go away or to fight among themselves. Likewise, the court at the heart of their empire sought to buy allegiance with honors, fancy titles, bales of silk, and streams of gold. Politics was the cunning art of providing just the right incentives to win over supporters and keep them loyal. Money, silk, and titles were the empire’s preferred instruments of governance and foreign policy, over swords and armies.”

[16]

The Byzantine civilization owed nothing to Rome. It inherited all its philosophical, scientific, poetic, mythological, and artistic tradition from classical Greece. Culturally, it was closer to Persia and Egypt than to Italy, which it treated as a colony. At the dawn of the second millenium AD, it had almost no recollection of its supposed Latin past, to the point that the most famous byzantine philosopher of the eleventh century,

Michael Psellos, confused Cicero with Caesar.

How does the textbook story of Constantine’s translatio imperii fit in this perspective? It doesn’t. In fact, the notion is highly problematic. Unwilling, for good reasons, to accept at face value the Christian tale that Constantine settled in Byzantium in order to leave Rome to the Pope, historians struggle to find a reasonable explanation for the transfer, and they generally settle for this one: after the old capital had fallen into irreversible decadence (soon to be sacked by the Gauls), Constantine decided to move the heart of the Empire closer to its most endangered borders. Does that make any sense? Even if it did, how plausible is the transfer of an imperial capital over a thousand miles, with senators, bureaucrats and armies, resulting in the metamorphosis of a Roman empire into another Roman empire with a totally different political structure, language, culture, and religion?

One of the major sources of this preposterous concept is the false Donation of Constantine. While it is admitted that this document was forged by medieval popes in order to justify their claim on Rome, its basic premise, the translation of the imperial capital to the East, has not been questioned. We suggest that Constantine’s translatio imperii was actually a mythological cover for the very real opposite movement of translatio studii, the transfer of Byzantine culture to the West that started before the crusades and evolved into systematic plunder after. Late medieval Roman culture rationalized and disguised its less than honorable Byzantine origin by the opposite myth of the Roman origin of Constantinople.

This will become clearer in the next article, but here is already one example of an insurmountable contradiction to the accepted filiation between the Eastern Roman Empire and the Western Roman Empire. One of the most fundamental and precious legacy of the Romans to our Western civilization is their tradition of civil law. Roman law is still the foundation of our legal system. How come, then, that Roman law was imported to Italy from Byzantium at the end of the eleventh century? Specialists like Harold Berman or Aldo Schiavone are adamant that knowledge of Roman laws had totally disappeared for 700 years in Western Europe, until a Byzantine copy of their compilation by Justinian (the

Digesta) was discovered around 1080 by Bolognese scholars. This “700-year long eclipse” of Roman law in the West, is an undisputed yet almost incomprehensible phenomenon

.[17]One obvious objection to the idea that the relationship between Rome and Constantinople has been inverted is that the Byzantines called themselves Romans (

Romaioi), and believed they were living in

Romania. Persians, Arabs and Turks called them

Roumis. Even the Greeks of the Hellenic Peninsula called themselves

Romaioi in Late Antiquity, despite their detestation of the Latins. This is taken as proof that the Byzantines considered themselves the heirs of the Roman Empire of the West, founded in Rome, Italy. But it is not. Strangely enough, mythography and etymology both suggest that, just like the name “Caesar”, the name “Rome” travelled from East to West, rather than the other way.

Romos, latinized in

Romus or

Remus, is a Greek word meaning “strong”. The Italian Romans were Etruscans from Lydia in Asia Minor. They were well aware of their eastern origin, the memory of which was preserved in their legends. According to the tradition elaborated by Virgil in his epic

Aeneid, Rome was founded by Aeneas from Troy, in the immediate vicinity of the Bosphorus. According to another version, Rome was founded by Romos, the son of Odysseus and Circe.

[18] The historian Strabo, supposedly living in the first century BC (but quoted only from the fifth century AD), reports that “another older tradition makes Rome an Arcadian colony,” and insists that “Rome itself was of Hellenic origin” (

Geographia V, 3). Denys of Halicarnassus in his

Roman Antiquities, declares “Rome is a Greek city.” His thesis is summed up by the syllogism: “The Romans descend from the Trojans. But the Trojans are of Greek origin. So the Romans are of Greek origin.”

The famous legend of Romulus and Remus, told by Titus Livy (I, 3), is generally considered of later origin. It could very well be an invention of the late Middle Age. Anatoly Fomenko, of whom we will have more to say later on, believes that its central theme, the simultaneous foundation of two cities, one by Romulus on the Palatine Hill, and the other by Remus on the Aventine, is a mythical reflection of the struggle for ascendency between the two Romes. As we shall see, the murder of Remus by Romulus is a fitting allegory of the events unfolding from the fourth crusade.

[19] Interestingly, that legend evokes the history of the brothers Valens and Valentinian, who are said to have reigned respectively over Constantinople and Rome from 364 to 378 (their story is known from one single author, Ammianus Marcellinus, a Greek writing in Latin). It happens that

valens is a Latin equivalent for the Greek

romos.We have started this article by suggesting that much of the history of the Western Roman Empire is of Renaissance invention. But as we progress in our investigation, another complementary hypothesis will emerge: much of the history of the Western Roman Empire is borrowed from the history of the Eastern Roman Empire, either by deliberate plagiarism, or by confusion resulting from the fact that the Byzantines called themselves Romans and their city Rome. The process can be inferred from some obvious duplicates. Here is one example, taken from Latin historian Jordanes, whose Origin and Deeds of the Goths is notoriously full of anachronisms: in 441, Attila crossed the Danube, invaded the Balkans, and threatened Constantinople, but could not take the city and retreated with an immense booty. Ten years later, the same Attila crossed the Alps, invaded Italy, and threatened Rome, but couldn’t take the city and retreated with an immense booty .

The mysterious origin of LatinAnother objection against questioning the existence of the Western Roman Empire is the spread of Latin throughout the Mediterranean world and beyond. It is admitted that Latin, originally the language spoken in the Latium, is the origin of French, Italian, Occitan, Catalan, Spanish and Portuguese, called “Western Romance Languages”. However, the amateur historian and linguist M. J. Harper has made the following remark:

“The linguistic evidence mirrors the geography with great precision: Portuguese resembles Spanish more than any other language; French resembles Occitan more than any other; Occitan resembles Catalan, Catalan resembles Spanish and so forth. So which was the Ur-language? Can’t tell; it could be any of them. Or it could be a language that has long since disappeared.

But the original language cannot have been Latin. All the Romance languages, even Portuguese and Italian, resemble one another more than any of them resemble Latin, and do so by a wide margin.”

[20]

For that reason, linguists postulate that

“Romance languages” do not derive directly from Latin, but from Vulgar Latin, the popular and colloquial sociolect of Latin spoken by soldiers, settlers, and merchants of the Roman Empire. What was Vulgar Latin, or proto-Romance, like? No one knows.

As a matter of fact, the language that most resembles Latin is Romanian, which, although divided in several dialects, constitutes by itself the only member of the Eastern branch of Romance languages. It is the only Romance language that has maintained archaic traits of Latin, such as the case system (endings of words depending on their role in the sentence) and the neutral gender.

[21]But how did Romanians come to speak Vulgar Latin? There is another mystery there. Part of the linguistic area of Romanian was conquered by Emperor Trajan in 106 AD, and formed the Roman province of Dacia for a mere 165 years. One or two legions were stationed in the South-West of Dacia, and, although not Italians, they are supposed to have communicated in Vulgar Latin and imposed their language to the whole country, even north of the Danube, where there was no Roman presence. What language did people speak in Dacia before the Romans conquered the south part of it? No one has a clue. The

“Dacian language” “is an extinct language, … poorly documented. … only one Dacian inscription is believed to have survived.” Only 160 Romanian words are hypothetically of Dacian origin. Dacian is believed to be closely related to

Thracian, itself “an extinct and poorly attested language.”

Let me repeat: The inhabitants of Dacia north of the Danube adopted Latin from the non-Italian legions that stationed on the lower part of their territory from 106 to 271 AD, and completely forgot their original language, to the point that no trace of it is left. They were so Romanized that their country came to be called Romania, and that Romanian is now closer to Latin than are other European Romance languages. Yet the Romans hardly ever occupied Dacia (on the map above, Dacia is not even counted as part of the Roman Empire). The next part is also extraordinary: Dacians, who had so easily given up their original language for Vulgar Latin, then became so attached to Vulgar Latin that the German invaders, who caused the Romans to retreat in 271, failed to impose their language. So did the Huns and, more surprisingly, the Slavs, who dominated the area since the seventh century and left many traces in the toponymy. Less than ten percent of Romanian words are of Slavic origin (but the Romanians adopted Slavonic for their liturgy).

One more thing: although Latin was a written language in the Empire, Romanians are believed to have never had a written language until the Middle Ages. The first document written in Romanian goes back to the sixteenth century, and it is written in Cyrillic alphabet.

Obviously, there is room for the following alternative theory: Latin is a language originating from Dacia; ancient Dacian did not vanish mysteriously but is the common ancestor of both Latin and modern Romanian. Dacian, if you will, is Vulgar Latin, which preceded Classical Latin. A likely explanation for the fact that Dacia is also called Romania is that it—rather than Italy—was the original home of the Romans who founded Constantinople.

[22] That would be consistent with the notion that the Roman language (Latin) remained the administrative language of the Eastern Empire until the sixth century AD, when it was abandoned for Greek, the language spoken by the majority of its subjects. That, in turn, is consistent with the character of Latin itself. Harper makes the following remark:

“Latin is not a natural language. When written, Latin takes up approximately half the space of written Italian or written French (or written English, German or any natural European language). Since Latin appears to have come into existence in the first half of the first millennium BC, which was the time when alphabets were first spreading through the Mediterranean basin, it seems a reasonable working hypothesis to assume that Latin was originally a shorthand compiled by Italian speakers for the purposes of written (confidential? commercial?) communication. This would explain:

a) the very close concordance between Italian and Latin vocabulary;

b) the conciseness of Latin in, for instance, dispensing with separate prepositions, compound verb forms and other ‘natural’ language impedimenta;

c) the unusually formal rules governing Latin grammar and syntax;

d) the lack of irregular, non-standard usages;

e) the unusual adoption among Western European languages of a specifically vocative case (‘Dear Marcus, re. you letter of…’).

[23]

The hypothesis that Latin was a “non-demotic” language, a koine of the empire, a cultural artifact developed for the purpose of writing, was first proposed by Russian researchers Igor Davidenko and Jaroslav Kesler in The Book of Civilizations (2001).

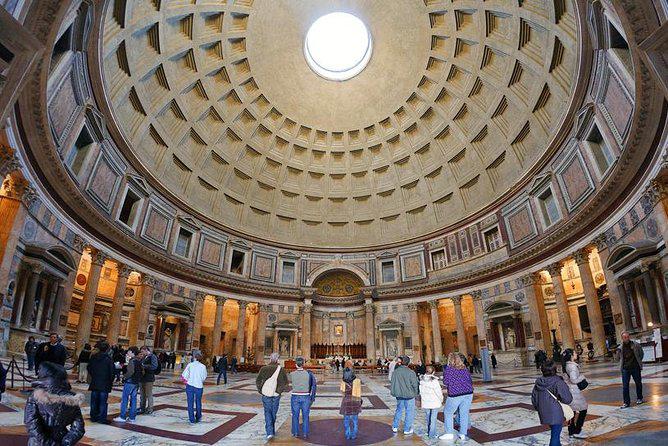

How old is ancient Roman architecture?The strongest objection against the theory that ancient Imperial Rome is a fiction is, of course, her many architectural vestiges. This subject will be more fully explored in a later article, but a quotation from Viscount James Bryce’s influential work, The Holy Roman Empire (1864), will point to the answer:

“The modern traveller, after his first few days in Rome, when he has looked out upon the Campagna from the summit of St. Peter’s, paced the chilly corridors of the Vatican, and mused under the echoing dome of the Pantheon, when he has passed in review the monuments of regal and republican and papal Rome, begins to seek for some relics of the twelve hundred years that lie between Constantine and Pope Julius the Second. ‘Where,’ he asks, ‘is the Rome of the Middle Ages, the Rome of Alberic and Hildebrand and Rienzi? the Rome which dug the graves of so many Teutonic hosts; whither the pilgrims flocked; whence came the commands at which kings bowed? Where are the memorials of the brightest age of Christian architecture, the age which reared Cologne and Rheims and Westminster, which gave to Italy the cathedrals of Tuscany and the wave-washed palaces of Venice?’ To this question there is no answer. Rome, the mother of the arts, has scarcely a building to commemorate those times.”

[24]

Officially, there is hardly a medieval vestige in Rome, and the same applies to other Italian cities believed to have been founded during Antiquity. François de Sarre, a French contributor to the field of research here presented, was first intrigued by the magnificent palace of the Roman emperor Diocletian (284-305 AD), in the center of the city of Split, today in Croatia. The Renaissance constructions are integrated to it in such a perfect architectural ensemble as to be almost indistinguishable. It is hard to believe that ten centuries separate the two stages of construction, as if the ancient buildings had been left untouched during the whole Middle Ages.

[25]

Also puzzling is the little-known fact that ancient Roman architecture used advanced technologies such as concretes of remarkable quality (read

here and

here), used for example to build the Pantheon’s beautifully preserved dome. The secrets of fabrication of Roman concrete is described in Vitruvius’ multi-volume work entitled

De architectura (first century BC). Medieval men, we are told, were totally ignorant of this technology, because “Vitruvius’ works were largely forgotten until 1414, when

De architectura was ‘rediscovered’ by the Florentine humanist Poggio Bracciolini in the library of Saint Gall Abbey” (

Wikipedia).

[26]

As a temporary conclusion: all the oddities that we have pointed out are like pieces of a puzzle that do not fit well within our conventional representation. We will later be able to assemble them into a more plausible picture. But before that, in the next article, we will focus on ecclesiastical literature from Late Antiquity to the Middle Ages, for it is the original source of the great historical distortion that later took a life of its own before being standardized as the dogma of modern chronology and historiography.

Notes

[1] Polydor Hochart,

De l’authenticité des Annales et des Histoires de Tacite, 1890 (on archive.org), pp. viii-ix.

[2] David Schaps, “The Found and Lost Manuscripts of Tacitus’

De Agricola,”

Classical Philology, Vol. 74, No. 1 (Jan., 1979), pp. 28-42, on

www.jstor.org. [4] Lynn Catterson, “Michelangelo’s ‘Laocoön?’,”

Artibus Et Historiae, vol. 26, n° 52, 2005, pp. 29–56, on

www.jstor.org. [5] David Carrette,

L’Invention du Moyen Âge. La plus grande falsification de l’histoire, Magazine

Top-Secret, Hors-série n°9, 2014.

[6] Jerry Brotton,

The Renaissance Bazaar: From the Silk Road to Michelangelo, Oxford UP, 2010, pp. 66-67.

[8] Jerry Brotton,

The Renaissance Bazaar, op. cit., pp. 66-67.

[9] It is never raised, for example, by Royston Lambert in his

Beloved and God: The Story of Hadrian and Antinous, Phoenix Giant, 1984.

[10] Petronius,

The Satyricon, trans. P. D. Walsh

, Oxford UP, 1997, “Introduction,” p. xxxv.

[11] Gédéon Huet, “Le Roman d’Apulée était-il connu au Moyen Âge ?”,

Le Moyen Âge, 22 (1909), pp. 23-28.

[13] Jean-Louis Brunaux,

The Celtic Gauls: Gods, Rites, and Santuaries, Routledge, 1987; David Henige, “He came, he saw, we counted: the historiography and demography of Caesar’s gallic numbers,”

Annales de démographie historique, 1998-1, pp. 215-242, on

www.persee.fr [14] Georges Dumézil,

Heur et malheur du guerrier.

Aspects mythiques de la fonction guerrière chez les Indo-Européens (1969), Flammarion, 1985, p. 66 and 16.

[15] Dux Francorum and

rex Francorum were used interchangibly for Peppin II, for example.

[16] Anthony Kaldellis,

Streams of Gold, Rivers of Blood: The Rise and Fall of Byzantium, 955 A.D. to the First Crusade, Oxford UP, 2019, p. xxvii.

[17] Harold J. Berman,

Law and Revolution, the Formation of the Western Legal Tradition, Harvard UP, 1983; Aldo Schiavone,

The Invention of Law in the West, Harvard UP, 2012.

[18] Sander M. Goldberg,

Epic in Republican Rome, Oxford UP, 1995, pp. 50-51.

[19] Anatoly T. Fomenko,

History: Fiction or Science? vol. 1, Delamere Publishing, 2003, p. 357.

[20] M. J. Harper,

The History of Britain Revealed, Icon Books, 2006, p. 116.

[22] We need to take into account that Southeastern Romania is located in the Pontic Steppe which, according to the widely held

Kurgan hypothesis, is the original home of the earliest proto-Indo-European speech community.

[23] M. J. Harper,

The History of Britain Revealed, op. cit., pp. 130-131.

[25] François de Sarre,

Mais où est donc passé le Moyen Âge ? Le récentisme, Hadès, 2013, available

here.

[26] More on Roman concrete in Lynne Lancaster,

Concrete Vaulted Construction in Imperial Rome: Innovations in Context, Cambridge UP, 2005.